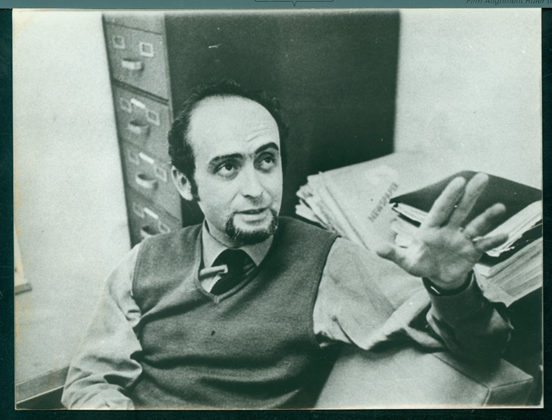

VLADO HERZOG was 38 years old when he was killed, under torture, at Doi–Codi’s premises in 1975 in São Paulo. At the time, he was editor of TV Cultura’s Hora da Notícia, and had voluntarily gone to give his testimony. From then on, a farce was set up in an attempt to cover up the murder by turning it into suicide, and a fierce struggle began for the truth to surface, turning the journalist into a kind of symbol against oppression and in defense of democracy. , whose last chapter was the condemnation of the Brazilian State by the OAS Inter–American Court of Human Rights, in 2018. It is to him that Itaú Cultural dedicates the 46th edition of the Occupation project, which has been revisiting the work and biography of major figures of Brazilian culture. The exhibition rightly goes beyond the political drama of the biographer. The starting point is not the dramatic end, but a streak of references to his public and private life, a route that somehow explains why he was brutally treated as an enemy of the regime. It recovers the story of a multifaceted figure, deeply interested in the course of the country at a particularly violent moment in its history and who saw in art, especially in cinema – the field of his greatest interest – a path of action and reflection.

Early on, visitors came across a careful selection of the photographs he was obsessively and rigorously taking. In the family holdings, more than 70 carefully identified slide boxes were found, containing images ranging from personal travel records to experiments of great formal richness, compositions marked by a keen eye, and the use of unusual angles and framings, such as that. which shows his son André, as a baby, in the middle of an intense red rose garden. The woman holding him, probably his wife Clarisse, practically leaves the scene to make the image more intense and disturbing.

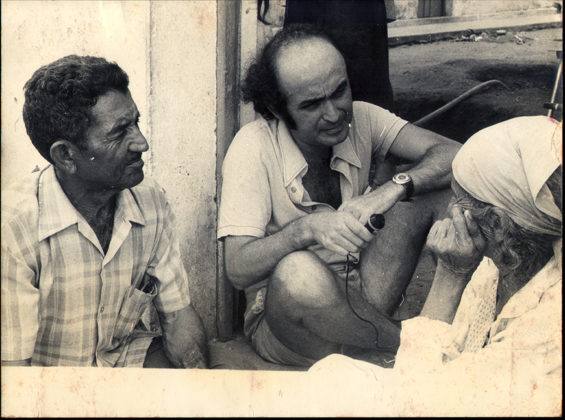

This first core, called Vlado Multimedia, also features a series of documents, testimonials from friends and fellow travelers, as well as Herzog’s own writings on cinema, witnessing both real action in this field and journalistic interest in defense. of a social use of language. Unfortunately, he was only able to direct a short film entitled Marimbimbas, but was already preparing to make a documentary about Canudos. Both photos taken during his field research in Bahia and Marimbás are part of the show. The catalog is also dedicated exclusively to his relationship with the cinema.

Her personal life, journalistic work and permanence as a symbol of the struggle against oppression (represented in works such as the action of Cildo Meireles, which stamps money with the question: “Who killed Herzog?”) Constitute the other nuclei of show. Over two years of research, which involved a team of eight researchers, in addition to the staff of Itaú Cultural and the Vladimir Herzog Institute – partners in the production of the show – thousands of data and documents were collected. Scattered throughout the exhibition space, the visitor comes across a wealth of rich elements such as facsimiles of his articles for various vehicles, posters and posthumous books honoring him, important documents relating to the Herzog Case such as the decision of Judge Márcio José de Moraes, who, in 1978, reversed the official version of suicide amid symbolic objects such as his typewriter and camera. Especially touching are items such as the Herzog family’s entry into Brazil in 1946 and a letter his father wrote to him narrating the family’s life during World War II, when they took refuge in Italy fleeing Yugoslavia and anti–Semitism. . Or the photograph of the newsroom of the State of S. Paulo, completely empty, on the day of his burial. A visual testimony to the enormous solidarity and commotion caused by his assassination by the military regime.

“It was a real gold digger. What we see here is just the surface”, says Luis Ludmer of the Herzog Institute and co–curator of the show along with Claudiney Ferreira, manager of the Audiovisual and Literature Center at Itaú Cultural. The idea is that all this material will serve as a basis for the construction of a website in the future, making access to all this volume of material permanent, which tends to become even wider with disclosures such as this one whose function is to It is not only about remembering the past and rescuing the figure of the engaged intellectual, so that he is never forgotten, but also building a model of resistance that is important in times of human rights retreat such as we are experiencing today. “We didn’t want anything funeral”, the curators say. Hence the option for an open museography, with the various nuclei in dialogue, marked by a certain lightness and rusticity.