Fully ready to be reopened after six years of renovations, the Museum of the Portuguese Language has already started to warm up its engines in anticipation of finally being able to open its doors, which should happen in late July or as soon as the pandemic allows. In addition to the physical reconstruction, which reassembled the structure destroyed by fire in 2015, the institution took the opportunity to conceptually reorganize itself and update content and communication strategies with the public. Overall, the project concept remains the same, based on an anthropological, historical and social perspective on the language, as outlined nearly 20 years ago.

As this is basically a virtual collection, the archives were not destroyed by fire and it was possible to reassemble a large part of the original exhibition. The possibility – and need – of redoing the exhibition from scratch brought, however, the opportunity to improve the permanent exhibition and update important aspects, incorporating transformations the language underwent in the period and proposing a reflection on contemporary debates related to identity issues, which has been intensely mobilizing the debate in recent years.

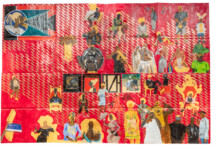

The institution also opened space for a more intense dialogue with various fields of culture, in addition to its intimate relationship with literature, incorporating new ways of thinking about language also based on everyday elements and other forms of expression, such as the arts. visuals. The result of this new approach is the museum’s first temporary exhibition, already accessible to small groups of visitors, entitled Língua Solta. “Since back then, we wanted to bring objects crossed by the language”, explains the institution’s special curator, Isa Grinspum Ferraz. After all, as Mozambican writer Mia Couto says in an online talk organized by the institution, “the Portuguese language does not work in the abstract”.

Among the novelties brought by the museum in this new guise are also the increment of the timeline, which runs through the history of the Portuguese language from Lazio, in ancient Rome, to the present day, with the problematization of fundamental moments in this trajectory, such as the year 1500 – in which testimonies of indigenous leaders such as Davi Kopenawa and Ailton Krenak were included, questioning the idea of discovery and explaining the process of invasion of already inhabited lands. In an almost opposite sense, the installation Nós da Língua Portuguesa (“we” both in terms of intertwining and of a pronoun that indicates a collectivity) highlights the importance of Portuguese as a language of liberation for African countries, allowing for a confluence of different peoples and dialects in a common project, experienced in countries like Mozambique, Angola and Cape Verde. Finally, among the novelties, Isa Grinspum highlights the new installation Falares, curated by Marcelino Freire and Roberta Estrela D’Alva, which creates a forest of canvases in which it is possible to take a walk, watching a web of testimonials, of iconic speeches, Portuguese accents and tribes.

When it opened in 2006, the massive use of virtual technology was one of the museum’s strong marks. Today, with a greater familiarity of people with this type of resource and the improvement of equipment, its protagonism seems more diluted. “The technology came to the service, to tell a story. As the language is impalpable, images and sounds are very useful. We do not seek interactivity for interactivity”, points out the curator. According to her, what matters is to stimulate the visitor’s interest as much as possible, making them leave the museum with more questions than they entered.

Faced with the challenges posed by the pandemic – which has been delaying its reopening and imposing the need to find new ways of contacting potential visitors – the museum has also been taking the opportunity to develop new forms of virtual interaction with the public. It took advantage of the international day of the Portuguese language to show a little of its new face, conducting a series of conversations and online presentations, which have already been seen by more than 15,000 viewers, with figures of great relevance in thinking about the role of language, such as Mia Couto, José Eduardo Agualusa and José Miguel Wisnik. It also launched cycles of virtual lectures and intends to establish cycles of debates, teacher training, film screenings, soirees, and other activities capable of spreading this production beyond the physical space.

Going outside is, in fact, one of the museum’s mottos, either in terms of content (to which digital communication can contribute a lot) or in spatial terms, connecting more intensely with the surroundings of its headquarters at Estação da Luz, through which hundreds of thousands of people walk every day.

Leia em português, clique aqui.