Sempre Gay: meninas de azul e meninos de rosa (Always Gay: girls in blue and boys in pink) addresses, conceptually and artistically, the resistance of young artists in situations of hatred, discrimination and erasures. Organized by Transarte, a gallery focused on LGBTq-themed projects and transgressive art, the exhibition brings together Liz Under, Bia Leite, Eduardo Mafea, Pedro Stephan, with works of pure militancy.

Contemporary art has developed a strategy of approximation with everyday life. The narrative of all of them does not separate the art of life, and the countersign to survival is to remain in a state of permanent alert in the face of a violent society for gays, women, blacks, indigenous and poor people. The works are born spontaneously, without worrying about the invoice and most of them mirror experienced situations. Liz Under, 24, opens the exhibition with photos of a performance with red sheets with vaginal crevices, held in her studio in Salvador, where she lived and worked. The essay starring her places the viewer as a voyeur of a sensual immersion. Liz lives in Araraquara and, in the three years she spent in Salvador he studied and began in art doing graffiti through the streets and street posters . It was there that she experienced on her skin the challenge of making a transgressive art. “Even within the Museum of Modern Art, where I took lithography classes, I did not escape an oppressive society.” Her aversion to the macho world inspired a drawing with the image of a cat with a penis crossed in his mouth, which angered her classmates. “They started treating me badly, calling the cat Miserable. The pressure was such that I came to dress as a man to be able to impose myself in that sexist and discriminatory environment.” Liz also suffered from the engravings of her bricked muses. In art history men paint naked women for male delight and I put my muses on paper in the search for the construction of their own pleasure, their own affection. When Liz exhibited these works at the 5th Bienal de Gravura Lívio Abramo in Araraquara, she was morally assaulted by a local journalist, known by his surname, Madalena. “Outraged, he offended me and classified my work as bitch art. I loved the name, I didn’t even have to think of another title, I took his.” She recalls that today in Brazil, we have the legitimation of violence that comes from those in power. The artist talks about a necro-political installed with social and political power to decide who lives and who dies. “The preferred targets are LGBTq, black and poor people.”

Just as Liz’s work is considered socially inappropriate by a conservative class, Bia Leite’s work also causes insults. She won the news pages when her painting Criança Viada was censored at the Queermuseu exhibition at the Santander Cultural Center in Porto Alegre. Under protests from some visitors the exhibition was closed and she was pursued and threatened with death. The show was only released after a collection program promoted by Parque Lage in Rio de Janeiro was created, where the show was exhibited with epic queues. The painting that horrified the people in Porto Alegre brings printed several prejudiced insults suffered by homosexuals since childhood.

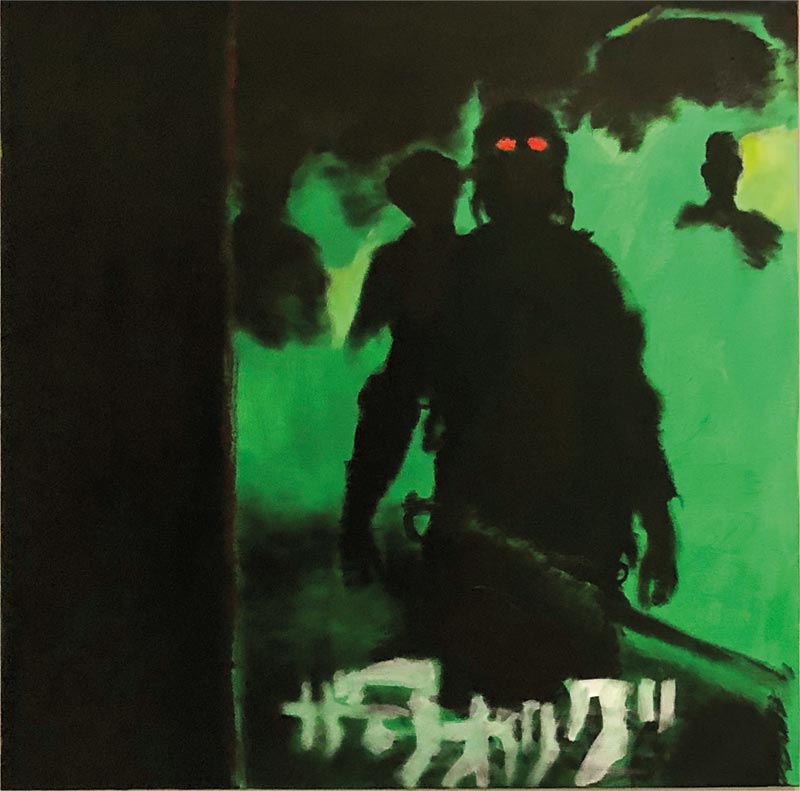

Bia was discovered and awarded by the Edital Transarte LGBT, in 2015 and has now just signed an exclusive contract with the gallery where she exhibits paintings inspired by alienists and a Japanese poster of horror film, by director John Carpenter. Her painting resembles the neo-expressionist traces of the 1980s, with corrosive colors and quotes from the pop universe.

Under also expressionist influence, Eduardo Mafea defends his work as a dive into the dualism of gay men and the compulsory connection to the macho universe of soccer, a sport appreciated by families as a symbol of virility. With other concerns, Pedro Stephan, passionate about Rio de Janeiro, author of several homoerotic photos, shows for the first time the essay Lâmpadas de Mercúrio, which can be seen as a non-narrative photonovel having as scenario the Parque do Flamengo, local where he has lived since childhood while riding there by bike. The 30 images from the essay show Stephan’s friends clicked in 2005 in love scenes. “I tried to subvert the cliché by proving that groping is not only slutty, it can also be romance.”

The director of Transarte, Maria Helena Peres writes in one of her catalogs that we need to be attentive to Brazil that has been proposing the gay cure, which closes exhibitions, beats and kills transvestites and creates monsters within the members of the LGBTq movement.