The Pivô space, based in the illustrious Copan building in São Paulo downtown, increasingly reinforces its commitment to encourage research and experiments in art, welcoming artists, curators and researchers in programs they offer. One of them, the Research Pivot, is intended for residences offered during the year to Brazilians or emerging foreigners, molded according to what each one is seeking, lasting approximately three or four months each.

In the almost six years since its creation, 145 artists from 20 different countries have participated, promoting activities that allow important exchanges among the participants themselves, but also with external agents, be they art critics or the public itself. In addition, the program has a series of institutional partnerships that allow for valuable exchanges, such as the CPPC (Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros), the British Council, Matadero Madrid, Centro Cultural São Paulo and ArtRio.

In the first residence of 2018, 13 artists were participating. They are: Adrián S. Bará, Anna Costa e Silva, Carolina Cordeiro, Carolina Maróstica, deco adjiman, Fernanda Feher, Gilson Rodrigues, Leandra Espirito Santo, Maya Weishof, Renan Marcondes, Rui Dias Monteiro, Tomaz Klotzel and Vanessa da Silva.

ARTE!Brasileiros talked to Feher about the theme of the project that she develops at Pivô:

A:B When did you decide that you wanted to be an artist?

Fernanda Feher: I spent my adolescence drawing and painting, until my theater director told me: “You have to study painting”. That is how he left Brazil and studied for ten years at the PRATT Institute, in Brooklyn, New York, where I established my vocation.

But I’ve always been an idealist, an activist. I was involved in day-to-day social and political concerns. At that time, Fernanda had a painter and Fernanda was an activist. I did volunteer work. It was a division that bothered me.

Over time I created the project “The women of there”, where I was able to synthesize my true vocation, to bring stories into my work. I was relieved.

A!B: How did you create this project?

I started researching Africa and see where I could collaborate. I first went to Tanzania at a Canadian school that taught adult women to help them create independence for their husbands or how to strengthen themselves individually and become economically independent in order to work. I was there for a month and a half.

There are several organizations I came in contact with, one based in London, ORCHID, which impressed me a lot. They address the issue of female mutilation worldwide.

I presented my original idea: to travel, interview and paint these women and use the sale of labor to support the work of the organization.

So I went to Kenya and, unintentionally, to a region near Tanzania.

The work is very difficult, because awareness of genital mutilation comes up against the cultural issue. Despite this being banned by the government, traditional families wait for the school holidays to send the girls all at the same time to do the mutilation. For them, mutilation is part of the “woman’s growth.” Some women, not mutilated, can not marry or are bullied. Mutilation is part of “being a woman.”

It happens between the ages of 9 and 14, during which time the woman begins to menstruate. The custom is so ingrained that some families today do the mutilation at the moment the girl is born, as a way to circumvent the law, which now prohibits.

In other cases the midwife herself, when an unmanaged woman is going to give birth, maim the woman in childbirth. Imagine the fright!

Bringing light on this cultural myth imposes a very serious job. It can not ban and not support education because mutilation would not be necessary in development, but traumatic. It is extremely complex.

A!B: You did not tell us this story, yet we were captured by your work even without it being literal. By force, by color. How do you explain this?

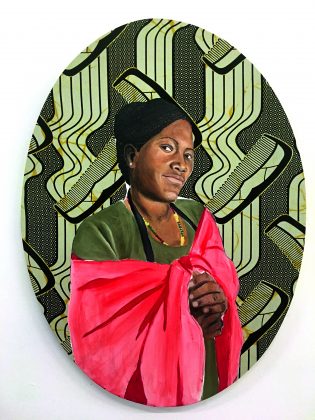

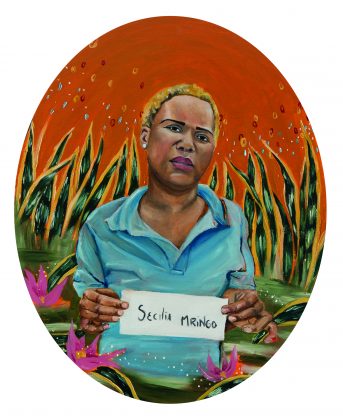

My portraits are of women who discuss all this. Some are mutilated, others are girls who came from the schools where we were to listen or collaborate and teach.

I have an interest in telling their stories, their strength and joy, and not necessarily showing the place where they are victims. I want to try to bring the other side into my work. I like that, of them being able to see as a whole.

I think if I painted mutilated vaginas I would not be collaborating in anything with this process and maybe no one would come to ask me who these women are…