*By Claudinei Roberto da Silva

Those responsible for the programming of Tomie Ohtake Institute, in São Paulo, coincided in their galleries the exhibitions of two artists of African descent: Pardo é Papel, itinerant exhibition by the artist from Rio de Janeiro Maxwell Alexandre; and Di Cavalcanti – Muralista, an exhibition by the renowned modernist painter, curated by Ivo Mesquita.

This “encounter” allows us to follow the strength of the history of Afro-Brazilian painting in two different moments and from distant but intertwined pictorial perspectives. A more patient look would perhaps notice important narrative coincidences between these seemingly disparate universes, but here we will focus on this young black artist who burst onto the national and international scene with peculiar force.

Since the end of the 19th century, in the West, art academies have established canons that lent importance – relative – to the various genres of painting. Thus, more meritorious and worthy of consideration (and consumption) would be the processes that resulted in works dedicated to the affirmation of the elites on duty, whether ecclesiastical or not. Works that portrayed these aristocracies would be guaranteed at the top of a hierarchical pyramid of aesthetic and political values.

Being represented was imperative and, in the absence of the monarch, the figure and authority expressed by painting or sculpture was revered. The representations of the king or nobles symbolically projected their powers and, therefore, were copiously carried out and distributed. Likewise, his deeds received great attention, since from his paintings of a historical character, warrior or pious deeds of the monarchs and their likes were disseminated.

Among us, this historical painting, which is almost necessarily epic in its appearance and pretension, was also practiced and some of these works still occupy a central place in the narratives that predict the birth of the Brazilian state and nation.

In our case, obeying the inherited and colonially imposed academic canons, these paintings show heroes in action, such as that Independência ou Morte, made in 1888 by Pedro Américo (1843- 1905) from Paraíba and currently belonging to the collection of the Paulista Museum of the University of São Paulo, where you see the still Prince Pedro flanked by an entourage and escorted by cavalrymen raising their swords and decreeing Brazilian independence from Portugal.

The other, Batalha do Avaí, also by Américo, was completed in 1877 and can be visited at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro. It represents a veritable crowd of soldiers engaged in a fierce battle and which has in the background a Duke, by the way, Caxias, whose uniform is open – as it appears, this provoked the displeasure of the portrayed -, who mounted on his white horse, coordinates haughty and distant the movements of “his” fatally victorious troop.

These works have in common the gigantic dimensions, the profuse number of soldiers who star in or support the actions described and, above all, the subordinate and peripheral role of characters representing the popular fraction of that society, whether black, women, indigenous or miserable white.

A Batalha do Avaí is notorious for the number of characters represented in it, for the technical prodigy involved in its realization and, of course, for the impressive description it makes of a crucial moment in the battle it describes. In that profusion of characters, bodies in dynamic and dramatic shock, in a central foreground and at the foot of the scene, we see the body of a black soldier who lies with a wounded head – from the split skull the encephalic mass escapes. The black people represented in this battle fight for the sovereignty of the country that kept them enslaved. However, the body dehumanized by slavery is the same one that sheds blood and viscera in that titanic combat presented by Pedro Américo.

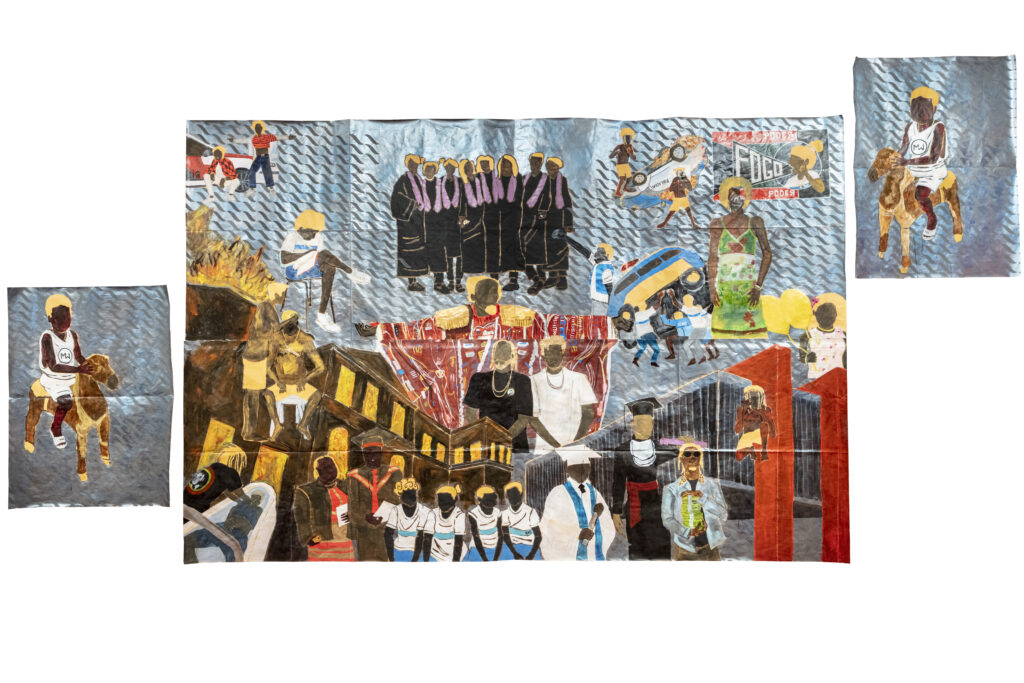

Maxwell Alexandre’s paintings exhibited in the Pardo é Papel show – initially shown at the Contemporary Art Museum in Lyon (France), in 2019, and later at the Rio Art Museum (mar) and at the Iberê Camargo Foundation, in Porto Alegre – also have an epic, grand, consecrating, and certainly historic character.

They were not made in Europe, like the one by Americo. They are not the result of a request from the State, nor were they painted in fine linen. Nor do they boast an ornate gilded frame that displays the weapons of the empire. On the contrary, Alexandre’s paintings exhibited at Tomie Ohtake Institute were made on a fragile support that is not even supported by a chassis. The fragility of this support, paper, is easily detected and perceived in the tears that were incorporated into the painting. Arte Povera, poor, that emerged in Italy in the 1950s and 1960s also praised the cheap material used by artists who adhered to this aesthetic. There as here, this choice highlights a political attitude.

As in the classics, Maxwell Alexandre’s painting also brings crowds in a dynamic movement. But, unlike other works, the bodies presented there are purposely all black, unmistakably black, and painted in everyday situations. And they are not anonymous. Despite not having their faces outlined, it is possible to identify the poet and samba artist Cartola, the demiurge Arthur Bispo do Rosário or Jean-Michel Basquiat, who join the myriad of other subjects in this fairy black scene that only on the flat surface of the paper seems chaotic , since the projected space is well composed of solid colors decorated with gold.

At the entrance to the gallery that houses the exhibition there is a huge painting representing a group of black people observing and commenting on a painting presented as a panel, beige or brown, a large empty rectangle yellow Naples, a very pale yellow. There is painting within painting, meta-painting. Maxwell Alexandre makes us contemplate people who, in turn, observe a panel (inside the panel) where a single color is seen. An acidic and intelligent commentary on the white cube, on the cultural institution that projects it and that reflects in a narcissistic way only the color of white allowed in this space, without mirroring blacks that also occupy it. If there are references to Basquiat in Alexandre’s painting, this influence does not take away the power of the artist’s works and, moreover, it is legitimate. It is nonetheless consecrating that young black and black female artists can refer to other equally black artists, excellent as their influences.

The opulence of gold over blue, iridescent gold over red, sparkling gold over green, are present in the composition of these paintings almost as a reminder of the precious metal that, prospected by the enslaved in the mines of Minas Gerais, made the wealth of many – less than those extract it. The gold frames the elements of pop culture, consumption, the symbols of social ascension promoted by sport, work, art and the sometimes inevitable delinquency in the path of the excluded.

It may be that we identify in Maxwell Alexandre’s paintings some festive character, of profane and sacred celebration. In this case, it is necessary to understand how much the party translates into resistance for that portion of the population that is the preferred target of the “stray bullets”, of necropolitics ammunition that mutilate families and liquidate young lives or even in the wombs of young mothers, but that it does not contain or dissipate the unsubmissive genius of this insurgent contemporary black Brazilian art.

Leia em português, clique aqui.