here is no fixed point from which to look at the work of Farnese de Andrade. His work, now reviewed on display at Almeida and Dale Gallery, not only contains a unique plastic and symbolic power, but also makes the history of Brazilian art more complex and interesting. Serving as a counterpoint to the official narrative, which sweeps under the rug any expression that escapes the idea of an abstract vocation in mid-twentieth-century Brazil, Farnese’s art deals with interdicts, phantoms, and archetypes, and brings out an uncomfortable subjectivity. As Denise Mattar, who is responsible for the selection of the almost 100 pieces in the show, his works “frolic in the bowels of the unconscious, and so fascinate, enchant, frighten and disturb.”

Dense, the exhibition spans a wide range of research and moments of the artist’s production. It seeks to illuminate the importance of its graphic production, little seen in the last decades but fundamental in its trajectory. For most of his career, Farnese was more valued as an illustrator and engraver, and it was not until the 1990s, and especially in the 21st century, that his three-dimensional production acquired an undeniable prominence, overshadowing other forms of expression. And yet, such a valuation was not enough to get him out of the way. It is curious that, despite being considered one of the most fertile Brazilian artists and has been revisited in several exhibitions, studies and publications (with emphasis on the encouraged book edited by Cosac Naify in 2002), it has been kept in the shade when it comes to recount the history of Brazilian art, being unjustly absent from important historical reviews, such as the 24th São Paulo Biennial, for example.

Such forgetfulness is often explained by the fact that his work presents a certain mismatch in relation to what was done hegemonically in his period of performance. He faced what Denise Mattar defines as “dictatorship of abstraction” and a vigorous resistance to forms of expression more linked to a figuration close to Expressionism and Surrealism. What supposedly brings him closer to authors who preceded him, like his master Guignard (whose indications secured him employment as an illustrator in several publications when he moved to Rio in 1946 to cure himself of a tuberculosis). However, the drive force of his work, the ability to deal with the torments and intimate agonies (not only his own but also of modern man in general) makes him closer to the contemporary art developed by succeeding generations than of his contemporaries.

Instead of considering the two-dimensional and three-dimensional productions of the artist as watertight blocks, Mattar’s curators try to smash the boundaries between languages, illuminating and putting into dialogue some of the most striking moments of this trajectory. “One thing is contained within the other. The Farnese of the 1990s are contained in the Farnese of the 1960s, “she argues. Leaving aside a rigid chronology, the visitor is presented to families of works, to moments marked in their trajectory. He always has before him an artist who seems to be constantly testing himself and his plastic, symbolic, metaphorical possibilities.

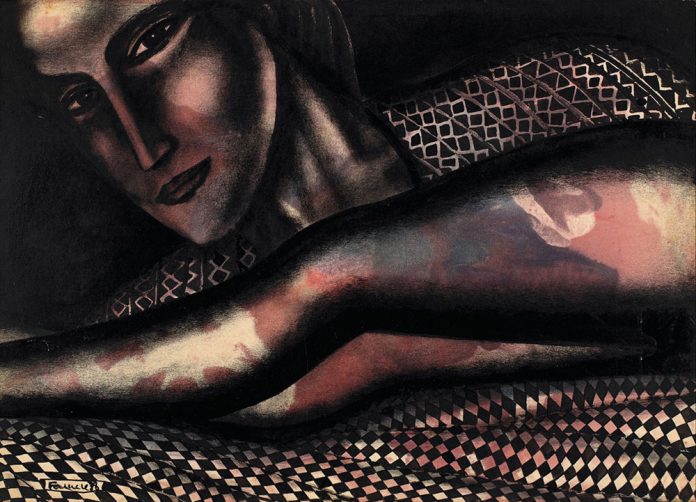

The oldest works of the exhibition constitute a nucleus disposed more at the bottom of the gallery. Here are the compulsive and intricate designs he said he did to “call sleep” and were called “Obsessive”; a well-behaved copy of the erotic phase he developed in the late 1960s; and one of three drawings, called “Censorship”, in which he makes an acid and ironic comment about the period of repression and gives an answer to the confiscation and destruction by the military of the works that he had sent to the 2 nd Biennial of Bahia two years earlier. These pieces guaranteed Farnese the Travel Prize at the Modern Art Hall of 1970, taking it to Europe, where it remained for the next five years.

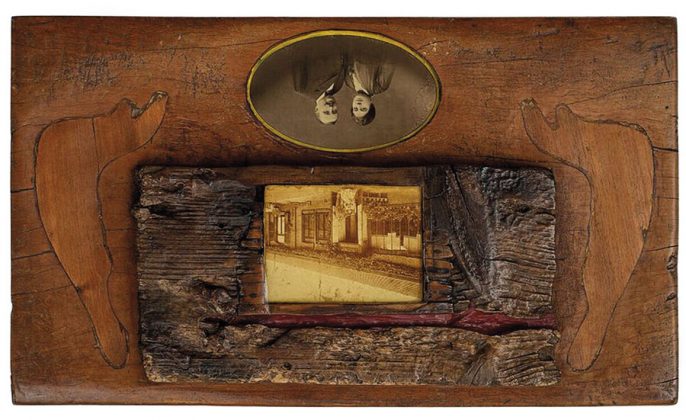

Two other important sets of two-dimensional works were panned by the show. The first of these is composed of 24 paintings made between 1963 and 1980. In addition to demonstrating his versatility – “he did everything at the same time”, Denise says -, this huge panel highlights some of the artist’s interests as a fascination with the sensuality of the human body (not just homoerotic) and their ability to reinvent ways of making art. In these cases, for example, he develops a particular technique, which he calls “transformed paint” and which consists of the application of watercolor mixed with a secret chemical on the wrong side of the already painted canvas, transferring to the work color spots and seductive forms , on which it had only partial control. The second is a set of monotypes made from objects found on the seashore or in landfills in the early 1960s and soon to be incorporated into their three-dimensional collages.

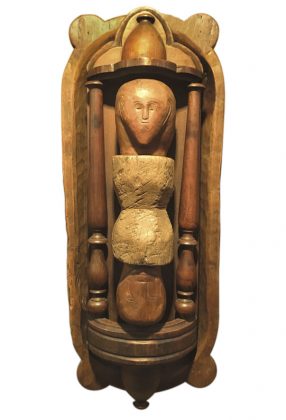

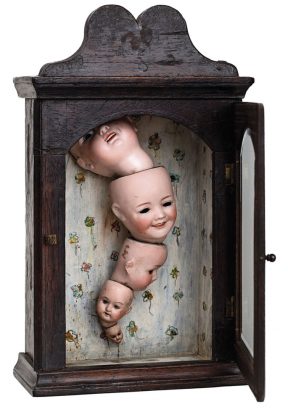

Started in 1964 and produced ceaselessly until his death in 1996, these pieces that gather wormwood; doll carcasses; saints of popular devotion; objects collected in antique shops, garbage or on the streets; shells found at random or images inherited from an uncle photographer form the body of the exhibition. They are embalmed in a resinous environment, enclosed in oratories that they adopt at the time they live in Barcelona, protected by glass beads or sheltered in the hollows of the traditional wooden troughs used in the popular cuisine of their native Minas Gerais, these compositions at the same time agonizing and seductive times – of an impressive formal preciosity – seem, as Mattar says, to “paralyze time”.

The themes are recurrent. There are annunciations, dives in affective memories related to paternal and maternal figures, a long series of works titled “We come from the sea”, and other fields of research to which it returns in an obsessive and compulsive way, as in an effort of purging and organization internal. There is something lugubrious, nostalgic, in this return to the past, that reopen wounds, leave feelings on display. As Charles Cosac well defined in the opening text of the catalog, “he fed himself nostalgia”.

And it infects us in this process. His pieces put to the flower of his skin emotions that should be buried, especially in a country that bet on the univocal way, redemptive of an art of right angles and abstract symbols, leaving behind their feet of clay, their wood gnawed by termites, a strange sensuality and his beheaded saints. In telling his stories, marked by terrible collective memories like the drowning of his two brothers some years before his birth and by a depressive state marked by several crises, Farnese echoes in each of them in a subjective way. However, it inevitably stirs intensely with feelings that go far beyond reason.

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025. Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025.

Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin e Jamile Coelho, a mostra reúne 20 artistas negras da diáspora africana e do continente africano, que se apropriam das artes visuais como campo de elaboração da memória e de reconstrução simbólica do mundo. Suas produções instauram um pensamento decolonial, no qual a arte atua como forma de escuta, reescrita e reexistência.

Participam: Amélia Sampaio, Barbara Asei Dantoni, Barbara Portailler, Beya Gille Gacha, Charlotte Yonga, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Enam Gbewonyo, Fabiana Ex-Souza, Gosette Lubondo, Josèfa Ntjam, Luana Vitra, Luisa Magaly, Luma Nascimento, Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt, Maria Lídia dos Santos Magliani, Myriam Mihindou, Na Chainkua Reindorf, Selly Raby Kane, Tuli Mekondjo e YêdaMaria.

Após itinerar por Bordeaux, Abidjan, Yaoundé e Antananarivo, a exposição chega a Salvador — cidade em que a herança africana se manifesta como fundamento estético e artístico — para instaurar um novo capítulo do projeto. No MUNCAB, essas artistas constroem um território de enunciação e reparação, no qual imagem, corpo e gesto tornam-se instrumentos de reconfiguração das narrativas históricas e de afirmação das subjetividades negras.

A exposição é uma realização do Ministério da Cultura, Petrobras e Embaixada da França no Brasil, em parceria com o MUNCAB, sob gestão da Amafro.

Serviço

Exposição | Memória: relatos de uma outra História

04 de novembro a 1º de março de 2026

Terça a domingo, das 10h às 16h30, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira: MUNCAB

R. das Vassouras, 25 - Centro Histórico, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá

Detalhes

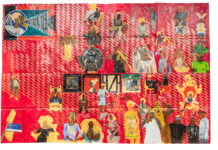

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá de Min, Heitor dos Prazeres, Juarez Paraíso, Lita Cerqueira, Maria Apparecida Urbano, Rafa Bqueer e Rosa Magalhães.

A mostra no edifício Pina Contemporânea expõe 200 obras dentre adereços, projetos de decoração e documentação histórica em fotografia e vídeo, além de comissionamentos de projetos inéditos dos artistas Adonai, Ana Lira e Ray Vianna.

Dividida em quatro temas – Fantasia, Trabalho, Poder e Cidade, “Trabalho de Carnaval” apresenta a maior festa popular do país como uma cadeia produtiva que envolve o trabalho das muitas mãos desde antes mesmo da festa acontecer, ao mesmo tempo em que alude à precariedade e invisibilidade desses profissionais.

NÚCLEOS TEMÁTICOS

O núcleo Fantasia faz referência a dois elementos característicos do carnaval: o ato de se fantasiar e a força da imaginação. Projetos e croquis integram a parte central da Grande Galeria, como os estudos de J. Cunha para o carnaval de Salvador e Joana Lira para as decorações de rua do Recife.

Discussões sobre as condições de trabalho da festa são apresentadas no núcleo Trabalho, no qual são apresentadas obras que trazem à tona a representatividade dos trabalhadores.

A relação entre carnaval e espaço urbano ou rural aparece no núcleo Cidade por meio de representações de blocos, cordões, afoxés e outras formas de cortejos. O núcleo reúne obras como as fotografias realizadas por Diego Nigro no bloco de carnaval Galo da Madrugada (2025).

Por fim, o núcleo Poder celebra os encontros de trabalhadores dos canaviais em Pernambuco transformando-se em reis e rainhas do maracatu, assim como mulheres negras e grupos periféricos marginalizados se tornando, por alguns dias, as figuras de comando durante a festa na Bahia: Deusas de Ébano, Reis Momos, Rainhas do Carnaval.

Serviço

Exposição | Trabalho de Carnaval

De 8 de novembro de 2025 a 12 de abril de 2026

Quarta a segunda, das 10h às 18h

Período

Local

Pinacoteca Contemporânea

Av. Tiradentes, 273, Luz, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas.

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas. Os trabalhos, desenvolvidos com técnicas distintas como pintura, desenho, instalação e filme, dão continuidade à investigação do artista sobre a construção da identidade nacional, e suas contradições e influências, por meio de ícones e símbolos presentes na cultura brasileira.

O título da exposição surge da ideia de nascimento como marco de um momento, de uma nova existência sobre a Terra. Este evento milagroso também carrega a contrapartida da fortuna e da sorte, que nos acompanha desde a concepção. Para Obá, “Estar sujeito a isso não diz a respeito de uma escolha. Estar sujeito a isso diz a respeito de uma irreverência ao inevitável. Então, o que podemos fazer é demarcar essas várias sortes através do rito, da celebração, do símbolo, da linguagem.”

Cada obra que compõe a exposição confere a essa tentativa de situar a ideia de sorte, fortuna, ora como uma prece, ora com um ritual que celebra isso.

Uma instalação inédita, localizada em um espaço fechado, no fundo da galeria, se refere diretamente a ideia de jogo e de sorte. Nela, colunas de búzios se derramam sobre peneiras de bronze douradas, carregando ovos de cerâmica pintados de vermelho. Os búzios representam elementos de tentativa de leitura da sorte, do destino e da sina, e simbolizam a moeda de troca, que também se transforma em oferenda. Na disposição que se encontram no espaço, os búzios formam colunas que estão ascendendo, como um território de elevação espiritual e de ressignificação da vida ante ao que ela propõe de fatal.

Na entrada do espaço expositivo, um caminho de espadas de São Jorge e Iansã, conduzem até um novo objeto instalativo: um altar com dois troncos que simbolizam o pelourinho. Os troncos estão inteiramente cravejados de pregos — em um deles, os pregos estão voltados para fora; no outro, para dentro — simbolizando proteção e punição e a dificuldade de harmonizar tensões. Entre os pelourinhos, cabos suspendem uma cabeça de bronze com um prumo na ponta. Esta instalação é uma oferenda ao senhor do caminho, portanto, tem uma relação com Exu.

A instalação Ka’a porá (2024), apresentada pela primeira vez na mostra itinerante Finca-Pé: Estórias da terra no CCBB Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte e Brasília, ocupa lugar de destaque na exposição. Esculturas de pés, representando tanto o pé humano quanto o de uma árvore, enfatizam a conexão com o solo. A configuração da obra lembra um pequeno jardim, com troncos dispostos de forma aparentemente aleatória, cada um sugerindo uma direção diferente dentro de um labirinto. O título da instalação deriva do termo tupi ka’a porá, que se refere a um indivíduo que se estabelece e se ancora à terra. A expressão também remete à figura mítica da Caipora, protetora das florestas na mitologia indígena brasileira. Outro elemento simbólico da instalação revisita o conceito de poda, entendido aqui como um ato de violência que rompe com a vida e a natureza.

Telas de diferentes tamanhos e técnicas compõem a narrativa visual da mostra. Um conjunto de 22 pinturas de pequeno formato apresenta a leitura de Obá sobre o Tarô. Nas obras, o artista utiliza de uma mistura de técnicas junto a folhas de ouro, conferindo um tom mágico e fantasioso único às cartas do oráculo. Além dessas, a exposição reúne novas pinturas de grandes dimensões, bem como uma obra pintada diretamente sobre uma das paredes do espaço expositivo. Nessas peças, figuras e símbolos que compõem a identidade brasileira sugerem novas interpretações. A mostra também inclui desenhos inéditos feitos com carvão, nanquim, lápis e têmpera e sobre tela.

O filme Encantado (2024) apresenta uma performance do artista que propõe reflexões sobre sistemas simbólicos — especialmente os religiosos. A ação performática evoca uma perspectiva ritualística, centrada na figura do peregrino, que, em seu gesto, sintetiza elementos de crença, cultura e tradição associados ao imaginário do romeiro.

Com esse conjunto de obras, que atravessa diferentes mídias e simbologias, a exposição reafirma a potência da produção de Antonio Obá na construção de uma poética que investiga identidade, território e espiritualidade.

Serviço

Exposição | Nascimento

De 8 de novembro a 14 de março de 2026

Terça a sexta, das 11h às 19h, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Mendes Wood DM

Rua Barra Funda, 216, São Paulo – SP

Detalhes

Na exposição Tania Candiani: Subterrânea, na Vermelho, Tania Candiani, por meio de bordados, desenhos, vídeos, obra sonora e instalação, transforma as redes subterrâneas das raízes em uma cartografia

Detalhes

Na exposição Tania Candiani: Subterrânea, na Vermelho, Tania Candiani, por meio de bordados, desenhos, vídeos, obra sonora e instalação, transforma as redes subterrâneas das raízes em uma cartografia tátil de emaranhamentos, na qual a matéria se torna sinal das energias que permeiam o solo.

As obras da individual mapeiam essas teias vivas em que sistemas naturais, não humanos e sonoros convergem, revelando as vibrações e ressonâncias invisíveis que atravessam o domínio subterrâneo.

Cada bordado da série Roots Systems é construído em torno de uma linha do horizonte, uma fronteira entre o que vemos e o que permanece oculto, onde estruturas se expandem pelo solo formando redes que ultrapassam a escala da planta visível. O bordado à máquina carrega o som e a vibração dessas redes em constante movimento.

A mesma série se desdobra em dois conjuntos de desenhos, um em tinta spray e outro em nanquim. No primeiro, raízes de diferentes indivíduos da mesma espécie são gravadas em papel de algodão. São dípticos em que cada indivíduo ocupa uma moldura, mas ambos parecem à beira do toque, expandindo-se a partir de um centro comum. O sopro do spray sugere difusão e indefinição, criação e dissolução. O encontro entre os indivíduos se torna uma zona de passagem e de criação, um espaço intermediário onde algo se comunica, se transforma ou nasce. Candiani fala desses desenhos como expressões de uma comunicação celular, emaranhada, que se aproxima das nebulosas, como sinapses cósmicas.

Os desenhos a nanquim se baseiam em raízes superficiais, que são sistemas radiculares que se espalham próximos à superfície do solo, em vez de se desenvolverem em profundidade. São raízes que se expandem horizontalmente em busca de água e nutrientes em ambientes áridos e solos rasos, são redes que buscam sustento na escassez.

Diferentes campos do conhecimento, como a biologia, a filosofia e as artes, aproximam a arquitetura das raízes superficiais das redes neurais. Estruturalmente, essas raízes se expandem em múltiplas direções, formando tramas conectadas semelhantes às sinapses da malha cognitiva.

Assim como os neurônios trocam impulsos elétricos, as raízes comunicam-se por sinais químicos e bioelétricos entre si, e com fungos e bactérias do solo. Essa rede subterrânea atua como um “cérebro ecológico”, que percebe e adapta o organismo vegetal ao ambiente. Tanto a rede neural quanto o sistema radicular superficial configuram formas de vida rizomáticas, baseadas no emaranhamento: expansões laterais que constroem sentido e continuidade por meio da conexão.

A comunicação subterrânea também é o eixo das obras Subterra: Roots, um vídeo circular e uma paisagem sonora multicanal que ampliam a percepção dessa rede viva. O vídeo, circular como uma escotilha, apresenta um fluxo contínuo de raízes, fungos e microrganismos em movimento, em um mergulho gradual pelas camadas do solo. A paisagem sonora, composta por vibrações subsonoras de baixa frequência, cria uma atmosfera imersiva que evoca o zumbido inaudível das redes subterrâneas em movimento, como um campo de ressonância onde as diferentes matérias se comunicam.

Também integra Subterra: Roots um grande rizotron duplo, construído especialmente para a exposição, no qual crescem plantas de milho. O dispositivo — uma caixa com amplas janelas de vidro onde se desenvolvem as plantas — é utilizado em pesquisas científicas para observar o crescimento radicular e permite acompanhar, em tempo contínuo, o que normalmente permanece oculto no solo.

Nesse trabalho, o sistema radicular deixa de ser apenas representação e se apresenta como corpo vivo em transformação. Ao integrar o processo de crescimento vegetal à experiência expositiva, Candiani aproxima ciência e sensibilidade, incorporando o tempo do movimento subterrâneo que atravessa toda a mostra. Com o longo período de duração da exposição, o rizotron transformará a paisagem da montagem a cada visita a Subterrânea.

A exposição fica em cartaz até o dia 19 de dezembro de 2025 e entre 12 de janeiro e 13 de fevereiro de 2026.

Serviço

Exposição | Tania Candiani: Subterrânea

De 13 de novembro a 13 de fevereiro de 2026

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 17h

Período

Local

Galeria Vermelho

Rua Minas Gerais, 350, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A DAN Galeria apresenta a exposição O Brasil dos modernistas, com curadoria de Maria Alice Milliet. Reunindo cerca de 50 obras de emblemáticas de nomes fundamentais como Tarsila do Amaral,

Detalhes

A DAN Galeria apresenta a exposição O Brasil dos modernistas, com curadoria de Maria Alice Milliet. Reunindo cerca de 50 obras de emblemáticas de nomes fundamentais como Tarsila do Amaral, Di Cavalcanti, Cícero Dias, Victor Brecheret, Cândido Portinari, Guignard, Alfredo Volpi, Anita Malfatti e outros, a coletiva traça um panorama da arte moderna no país e destaca o papel do movimento que, a partir da década de 1920, redefiniu a linguagem artística nacional e acrescentou ao imaginário coletivo visões atualizadas do imaginário popular brasileiro.

O Brasil dos modernistas toma como ponto de partida das transformações que marcaram o surgimento da modernidade artística no Brasil, um movimento que se consolidou no confronto entre o conservadorismo cultural e o impulso de renovação de um país em transição. A Semana de Arte Moderna de 1922, é retomada aqui como marco simbólico desse embate: vaiada pelo público, expôs a resistência às novas linguagens e à ruptura com os padrões tradicionais, inaugurando uma produção voltada à atualização estética e à construção de uma identidade artística brasileira.

O percurso curatorial retrata como os primeiros modernistas, em busca de formação e reconhecimento, voltaram-se aos grandes centros artísticos da Europa. Foi a partir dessa experiência que muitos passaram a perceber a força e a originalidade da diversidade cultural brasileira para construção de suas próprias identidades artísticas. “Os nossos modernos não precisaram buscar em lugares exóticos os conteúdos populares ou étnicos que tanto encantavam os europeus. Encontraram em nossas paisagens e costumes os ingredientes para a constituição de uma visualidade de caráter nacional”, afirma a curadora Maria Alice Milliet.

Embora influenciada pelas vanguardas europeias, a arte moderna no Brasil manteve-se fiel à figuração. O contato com o movimento de “retorno à ordem”, no período entre guerras, levou os artistas a explorar linguagens expressionistas, cubistas e, mais tarde, surrealistas, em um processo que definiu as bases estéticas do primeiro modernismo brasileiro.

Dentre os destaques da mostra, está o Retrato de Judite (1944), de Alfredo Volpi. Pintado no ano em que o artista se casou com Benedita da Conceição, conhecida como Judite, o trabalho retrata sua esposa nua entre cortinas, de braços abertos, como se apresentasse as pinturas que a cercam. Volpi, que iniciou a carreira decorando fachadas paulistanas, desenvolveu uma linguagem própria, marcada pela geometrização e pelo uso refinado da cor. Seu trabalho simboliza a passagem da pintura figurativa para uma modernidade madura, iluminada e de forte identidade brasileira.

“É inegável que Tarsila, Di Cavalcanti, Cícero Dias, Rego Monteiro, Brecheret, Portinari, Guignard constituíram um corpus iconográfico identificado com o Brasil. Mais que isso, o modernismo acrescentou ao imaginário nacional visões atualizadas da nossa realidade sociocultural. Ou seja, quando pensamos na mulher brasileira, vem à nossa cabeça a sensualidade das morenas pintadas por Di Cavalcanti; a história da conquista do nosso território realiza-se no Monumento às Bandeiras, de Brecheret; nossos mitos são os de Tarsila; nossas praias são as de Pancetti; e as festas populares têm no colorido das bandeirinhas de Volpi sua melhor expressão”, completa Maria Alice Milliet sobre o eixo expositivo.

Ao reunir obras fundamentais do período, a mostra O Brasil dos modernistas destaca a relevância histórica e cultural do movimento que redefiniu os rumos da arte no país. A coletiva reforça o papel dessa geração de artistas na construção de uma identidade visual e reafirma a atualidade de seu legado na formação do que se entende por brasilidade.

Artistas presentes

Alberto da Veiga Guignard, Alfredo Volpi, Anita Malfatti, Candido Portinari, Cícero Dias, Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, Ernesto De Fiori, Ismael Nery, José Pancetti, Tarsila do Amaral, Vicente do Rego Monteiro e Victor Brecheret.

Serviço

Exposição | O Brasil dos modernistas

De 19 de novembro a 19 de janeiro

De segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, aos sábados, das 10h às 13h

Período

Local

DAN Galeria

Rua Estados Unidos, 1638 01427-002 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao longo dos anos, consolidou-se como cineasta, mas a fotografia continuou presente em sua trajetória, seja em seus filmes, seja nas instalações artísticas que produziu no século 21. Essa faceta de sua obra, ainda menos conhecida pelo público, é apresentada na mostra Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema, que abre no IMS Paulista, com entrada gratuita.

A exposição Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema reúne cerca de 200 fotografias tiradas por Varda, principalmente, entre as décadas de 1950 e 1960. O conjunto traz imagens clicadas em viagens, incluindo registros inéditos na China, em 1957, fotos em Cuba, no contexto pós-revolução, e nos EUA, onde a artista documentou os Panteras Negras. Há ainda fotos feitas em Paris, como as de uma peça encenada pelos Griôs, primeira companhia de teatro negro na cidade. Em diálogo, a mostra apresenta trechos de filmes da autora, enfatizando como o comprometimento social, o olhar afetuoso e o humor caracterizam a sua produção.

Serviço

Exposição | Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema

De 29 de novembro a 12 de abril de 2026

Terça a domingo e feriados das 10h às 20h (fechado às segundas)

Período

Local

IMS - Instituto Moreira Salles

Avenida Paulista, 2424 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres obras e documentos, incluindo pinturas, manuscritos inéditos, maquetes, desenhos e os célebres brinquedos de madeira produzidos pela família do artista uruguaio.

É a primeira vez que esse conjunto tão amplo e diversificado do artista é apresentado no Brasil, com peças que deixarão pela primeira vez as reservas técnicas do museu uruguaio, revelando ao público aspectos pouco conhecidos da produção do artista.

Com curadoria de Saulo di Tarso em colaboração com o Museo Torres García, a mostra aprofunda o entendimento sobre o “universalismo construtivo” e apresenta Torres García como um pensador de alcance global. A pedagogia do Taller Torres García, que defendia que os artistas da América Latina desenvolvessem uma arte própria sem depender das influências europeias e norte-americanas, também é explicada na exposição. A proposta era incentivar cada artista a buscar suas raízes, símbolos e referências locais, criando uma produção mais autêntica e conectada com a cultura do continente — algo que dialoga diretamente com a seleção presente na exposição.

Instituições como o Museo Torres García (Uruguai), o Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Barcelona), o Institut Valencià d’Art Modern [Instituto de Arte Moderna de Valência], o Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (Chile), além de coleções brasileiras como o MASP e a Pinacoteca de São Paulo, contribuem com empréstimos essenciais.

Este projeto conta com incentivo da Lei Federal de Incentivo à Cultura – Lei Rouanet e patrocínio da BB Asset.

Serviço

Exposição | Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos

De 10 de dezembro a 09 de março de 2026

Aberto todos os dias, das 9h às 20h, exceto às terças

Período

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025. Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025.

Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin e Jamile Coelho, a mostra reúne 20 artistas negras da diáspora africana e do continente africano, que se apropriam das artes visuais como campo de elaboração da memória e de reconstrução simbólica do mundo. Suas produções instauram um pensamento decolonial, no qual a arte atua como forma de escuta, reescrita e reexistência.

Participam: Amélia Sampaio, Barbara Asei Dantoni, Barbara Portailler, Beya Gille Gacha, Charlotte Yonga, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Enam Gbewonyo, Fabiana Ex-Souza, Gosette Lubondo, Josèfa Ntjam, Luana Vitra, Luisa Magaly, Luma Nascimento, Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt, Maria Lídia dos Santos Magliani, Myriam Mihindou, Na Chainkua Reindorf, Selly Raby Kane, Tuli Mekondjo e YêdaMaria.

Após itinerar por Bordeaux, Abidjan, Yaoundé e Antananarivo, a exposição chega a Salvador — cidade em que a herança africana se manifesta como fundamento estético e artístico — para instaurar um novo capítulo do projeto. No MUNCAB, essas artistas constroem um território de enunciação e reparação, no qual imagem, corpo e gesto tornam-se instrumentos de reconfiguração das narrativas históricas e de afirmação das subjetividades negras.

A exposição é uma realização do Ministério da Cultura, Petrobras e Embaixada da França no Brasil, em parceria com o MUNCAB, sob gestão da Amafro.

Serviço

Exposição | Memória: relatos de uma outra História

04 de novembro a 1º de março de 2026

Terça a domingo, das 10h às 16h30, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira: MUNCAB

R. das Vassouras, 25 - Centro Histórico, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá

Detalhes

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá de Min, Heitor dos Prazeres, Juarez Paraíso, Lita Cerqueira, Maria Apparecida Urbano, Rafa Bqueer e Rosa Magalhães.

A mostra no edifício Pina Contemporânea expõe 200 obras dentre adereços, projetos de decoração e documentação histórica em fotografia e vídeo, além de comissionamentos de projetos inéditos dos artistas Adonai, Ana Lira e Ray Vianna.

Dividida em quatro temas – Fantasia, Trabalho, Poder e Cidade, “Trabalho de Carnaval” apresenta a maior festa popular do país como uma cadeia produtiva que envolve o trabalho das muitas mãos desde antes mesmo da festa acontecer, ao mesmo tempo em que alude à precariedade e invisibilidade desses profissionais.

NÚCLEOS TEMÁTICOS

O núcleo Fantasia faz referência a dois elementos característicos do carnaval: o ato de se fantasiar e a força da imaginação. Projetos e croquis integram a parte central da Grande Galeria, como os estudos de J. Cunha para o carnaval de Salvador e Joana Lira para as decorações de rua do Recife.

Discussões sobre as condições de trabalho da festa são apresentadas no núcleo Trabalho, no qual são apresentadas obras que trazem à tona a representatividade dos trabalhadores.

A relação entre carnaval e espaço urbano ou rural aparece no núcleo Cidade por meio de representações de blocos, cordões, afoxés e outras formas de cortejos. O núcleo reúne obras como as fotografias realizadas por Diego Nigro no bloco de carnaval Galo da Madrugada (2025).

Por fim, o núcleo Poder celebra os encontros de trabalhadores dos canaviais em Pernambuco transformando-se em reis e rainhas do maracatu, assim como mulheres negras e grupos periféricos marginalizados se tornando, por alguns dias, as figuras de comando durante a festa na Bahia: Deusas de Ébano, Reis Momos, Rainhas do Carnaval.

Serviço

Exposição | Trabalho de Carnaval

De 8 de novembro de 2025 a 12 de abril de 2026

Quarta a segunda, das 10h às 18h

Período

Local

Pinacoteca Contemporânea

Av. Tiradentes, 273, Luz, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas.

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas. Os trabalhos, desenvolvidos com técnicas distintas como pintura, desenho, instalação e filme, dão continuidade à investigação do artista sobre a construção da identidade nacional, e suas contradições e influências, por meio de ícones e símbolos presentes na cultura brasileira.

O título da exposição surge da ideia de nascimento como marco de um momento, de uma nova existência sobre a Terra. Este evento milagroso também carrega a contrapartida da fortuna e da sorte, que nos acompanha desde a concepção. Para Obá, “Estar sujeito a isso não diz a respeito de uma escolha. Estar sujeito a isso diz a respeito de uma irreverência ao inevitável. Então, o que podemos fazer é demarcar essas várias sortes através do rito, da celebração, do símbolo, da linguagem.”

Cada obra que compõe a exposição confere a essa tentativa de situar a ideia de sorte, fortuna, ora como uma prece, ora com um ritual que celebra isso.

Uma instalação inédita, localizada em um espaço fechado, no fundo da galeria, se refere diretamente a ideia de jogo e de sorte. Nela, colunas de búzios se derramam sobre peneiras de bronze douradas, carregando ovos de cerâmica pintados de vermelho. Os búzios representam elementos de tentativa de leitura da sorte, do destino e da sina, e simbolizam a moeda de troca, que também se transforma em oferenda. Na disposição que se encontram no espaço, os búzios formam colunas que estão ascendendo, como um território de elevação espiritual e de ressignificação da vida ante ao que ela propõe de fatal.

Na entrada do espaço expositivo, um caminho de espadas de São Jorge e Iansã, conduzem até um novo objeto instalativo: um altar com dois troncos que simbolizam o pelourinho. Os troncos estão inteiramente cravejados de pregos — em um deles, os pregos estão voltados para fora; no outro, para dentro — simbolizando proteção e punição e a dificuldade de harmonizar tensões. Entre os pelourinhos, cabos suspendem uma cabeça de bronze com um prumo na ponta. Esta instalação é uma oferenda ao senhor do caminho, portanto, tem uma relação com Exu.

A instalação Ka’a porá (2024), apresentada pela primeira vez na mostra itinerante Finca-Pé: Estórias da terra no CCBB Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte e Brasília, ocupa lugar de destaque na exposição. Esculturas de pés, representando tanto o pé humano quanto o de uma árvore, enfatizam a conexão com o solo. A configuração da obra lembra um pequeno jardim, com troncos dispostos de forma aparentemente aleatória, cada um sugerindo uma direção diferente dentro de um labirinto. O título da instalação deriva do termo tupi ka’a porá, que se refere a um indivíduo que se estabelece e se ancora à terra. A expressão também remete à figura mítica da Caipora, protetora das florestas na mitologia indígena brasileira. Outro elemento simbólico da instalação revisita o conceito de poda, entendido aqui como um ato de violência que rompe com a vida e a natureza.

Telas de diferentes tamanhos e técnicas compõem a narrativa visual da mostra. Um conjunto de 22 pinturas de pequeno formato apresenta a leitura de Obá sobre o Tarô. Nas obras, o artista utiliza de uma mistura de técnicas junto a folhas de ouro, conferindo um tom mágico e fantasioso único às cartas do oráculo. Além dessas, a exposição reúne novas pinturas de grandes dimensões, bem como uma obra pintada diretamente sobre uma das paredes do espaço expositivo. Nessas peças, figuras e símbolos que compõem a identidade brasileira sugerem novas interpretações. A mostra também inclui desenhos inéditos feitos com carvão, nanquim, lápis e têmpera e sobre tela.

O filme Encantado (2024) apresenta uma performance do artista que propõe reflexões sobre sistemas simbólicos — especialmente os religiosos. A ação performática evoca uma perspectiva ritualística, centrada na figura do peregrino, que, em seu gesto, sintetiza elementos de crença, cultura e tradição associados ao imaginário do romeiro.

Com esse conjunto de obras, que atravessa diferentes mídias e simbologias, a exposição reafirma a potência da produção de Antonio Obá na construção de uma poética que investiga identidade, território e espiritualidade.

Serviço

Exposição | Nascimento

De 8 de novembro a 14 de março de 2026

Terça a sexta, das 11h às 19h, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Mendes Wood DM

Rua Barra Funda, 216, São Paulo – SP

Detalhes

Na exposição Tania Candiani: Subterrânea, na Vermelho, Tania Candiani, por meio de bordados, desenhos, vídeos, obra sonora e instalação, transforma as redes subterrâneas das raízes em uma cartografia

Detalhes

Na exposição Tania Candiani: Subterrânea, na Vermelho, Tania Candiani, por meio de bordados, desenhos, vídeos, obra sonora e instalação, transforma as redes subterrâneas das raízes em uma cartografia tátil de emaranhamentos, na qual a matéria se torna sinal das energias que permeiam o solo.

As obras da individual mapeiam essas teias vivas em que sistemas naturais, não humanos e sonoros convergem, revelando as vibrações e ressonâncias invisíveis que atravessam o domínio subterrâneo.

Cada bordado da série Roots Systems é construído em torno de uma linha do horizonte, uma fronteira entre o que vemos e o que permanece oculto, onde estruturas se expandem pelo solo formando redes que ultrapassam a escala da planta visível. O bordado à máquina carrega o som e a vibração dessas redes em constante movimento.

A mesma série se desdobra em dois conjuntos de desenhos, um em tinta spray e outro em nanquim. No primeiro, raízes de diferentes indivíduos da mesma espécie são gravadas em papel de algodão. São dípticos em que cada indivíduo ocupa uma moldura, mas ambos parecem à beira do toque, expandindo-se a partir de um centro comum. O sopro do spray sugere difusão e indefinição, criação e dissolução. O encontro entre os indivíduos se torna uma zona de passagem e de criação, um espaço intermediário onde algo se comunica, se transforma ou nasce. Candiani fala desses desenhos como expressões de uma comunicação celular, emaranhada, que se aproxima das nebulosas, como sinapses cósmicas.

Os desenhos a nanquim se baseiam em raízes superficiais, que são sistemas radiculares que se espalham próximos à superfície do solo, em vez de se desenvolverem em profundidade. São raízes que se expandem horizontalmente em busca de água e nutrientes em ambientes áridos e solos rasos, são redes que buscam sustento na escassez.

Diferentes campos do conhecimento, como a biologia, a filosofia e as artes, aproximam a arquitetura das raízes superficiais das redes neurais. Estruturalmente, essas raízes se expandem em múltiplas direções, formando tramas conectadas semelhantes às sinapses da malha cognitiva.

Assim como os neurônios trocam impulsos elétricos, as raízes comunicam-se por sinais químicos e bioelétricos entre si, e com fungos e bactérias do solo. Essa rede subterrânea atua como um “cérebro ecológico”, que percebe e adapta o organismo vegetal ao ambiente. Tanto a rede neural quanto o sistema radicular superficial configuram formas de vida rizomáticas, baseadas no emaranhamento: expansões laterais que constroem sentido e continuidade por meio da conexão.

A comunicação subterrânea também é o eixo das obras Subterra: Roots, um vídeo circular e uma paisagem sonora multicanal que ampliam a percepção dessa rede viva. O vídeo, circular como uma escotilha, apresenta um fluxo contínuo de raízes, fungos e microrganismos em movimento, em um mergulho gradual pelas camadas do solo. A paisagem sonora, composta por vibrações subsonoras de baixa frequência, cria uma atmosfera imersiva que evoca o zumbido inaudível das redes subterrâneas em movimento, como um campo de ressonância onde as diferentes matérias se comunicam.

Também integra Subterra: Roots um grande rizotron duplo, construído especialmente para a exposição, no qual crescem plantas de milho. O dispositivo — uma caixa com amplas janelas de vidro onde se desenvolvem as plantas — é utilizado em pesquisas científicas para observar o crescimento radicular e permite acompanhar, em tempo contínuo, o que normalmente permanece oculto no solo.

Nesse trabalho, o sistema radicular deixa de ser apenas representação e se apresenta como corpo vivo em transformação. Ao integrar o processo de crescimento vegetal à experiência expositiva, Candiani aproxima ciência e sensibilidade, incorporando o tempo do movimento subterrâneo que atravessa toda a mostra. Com o longo período de duração da exposição, o rizotron transformará a paisagem da montagem a cada visita a Subterrânea.

A exposição fica em cartaz até o dia 19 de dezembro de 2025 e entre 12 de janeiro e 13 de fevereiro de 2026.

Serviço

Exposição | Tania Candiani: Subterrânea

De 13 de novembro a 13 de fevereiro de 2026

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 17h

Período

Local

Galeria Vermelho

Rua Minas Gerais, 350, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao longo dos anos, consolidou-se como cineasta, mas a fotografia continuou presente em sua trajetória, seja em seus filmes, seja nas instalações artísticas que produziu no século 21. Essa faceta de sua obra, ainda menos conhecida pelo público, é apresentada na mostra Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema, que abre no IMS Paulista, com entrada gratuita.

A exposição Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema reúne cerca de 200 fotografias tiradas por Varda, principalmente, entre as décadas de 1950 e 1960. O conjunto traz imagens clicadas em viagens, incluindo registros inéditos na China, em 1957, fotos em Cuba, no contexto pós-revolução, e nos EUA, onde a artista documentou os Panteras Negras. Há ainda fotos feitas em Paris, como as de uma peça encenada pelos Griôs, primeira companhia de teatro negro na cidade. Em diálogo, a mostra apresenta trechos de filmes da autora, enfatizando como o comprometimento social, o olhar afetuoso e o humor caracterizam a sua produção.

Serviço

Exposição | Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema

De 29 de novembro a 12 de abril de 2026

Terça a domingo e feriados das 10h às 20h (fechado às segundas)

Período

Local

IMS - Instituto Moreira Salles

Avenida Paulista, 2424 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres obras e documentos, incluindo pinturas, manuscritos inéditos, maquetes, desenhos e os célebres brinquedos de madeira produzidos pela família do artista uruguaio.

É a primeira vez que esse conjunto tão amplo e diversificado do artista é apresentado no Brasil, com peças que deixarão pela primeira vez as reservas técnicas do museu uruguaio, revelando ao público aspectos pouco conhecidos da produção do artista.

Com curadoria de Saulo di Tarso em colaboração com o Museo Torres García, a mostra aprofunda o entendimento sobre o “universalismo construtivo” e apresenta Torres García como um pensador de alcance global. A pedagogia do Taller Torres García, que defendia que os artistas da América Latina desenvolvessem uma arte própria sem depender das influências europeias e norte-americanas, também é explicada na exposição. A proposta era incentivar cada artista a buscar suas raízes, símbolos e referências locais, criando uma produção mais autêntica e conectada com a cultura do continente — algo que dialoga diretamente com a seleção presente na exposição.

Instituições como o Museo Torres García (Uruguai), o Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Barcelona), o Institut Valencià d’Art Modern [Instituto de Arte Moderna de Valência], o Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (Chile), além de coleções brasileiras como o MASP e a Pinacoteca de São Paulo, contribuem com empréstimos essenciais.

Este projeto conta com incentivo da Lei Federal de Incentivo à Cultura – Lei Rouanet e patrocínio da BB Asset.

Serviço

Exposição | Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos

De 10 de dezembro a 09 de março de 2026

Aberto todos os dias, das 9h às 20h, exceto às terças