“Alright, alright. Don’t forget what you see here”. That was the comment made by one of the patrons of the Kobune bar to Munemasa Takahashi, on April 26, 2011, after he said he was not in Miyagi Prefecture (Japan) as yet another volunteer, collaborating on the site that had been reached a month ago and a half before his visit, due to an earthquake of magnitude 9.1, which moved walls of water that bombarded the island’s coast.

Takahashi, who had studied photography and built a life around it, felt helpless with his helplessness in the face of disaster. “When the lifelines – electricity, gas and water – had stopped, when there was no food or fuel, and no way to keep warm, there was nothing photography could do to help them. The photographs just seemed to be documenting and delivering the scenes of the horrific event to the people in safe places”, he would later explain, about the coverage of the tragedy in images, in the prologue to the book Tsunami, Photographs and Then, organized later by him in an effort to portray the construction of the Memory Salvage and Lost & Found projects in a bilingual publication – Japanese and English – offering rich details, interviews with visitors to the exhibitions and, of course, some of the exposed images.

Before that, his greatest hope for avoiding inertia in the face of the tragedy was to travel to one of the least affected areas in the province, to spend money with local traders and to try to move the local economy a little.

“Please let me know if you can help”, said a message spread over the networks eight days after his visit. It was a call by volunteers to integrate the cleaning and cataloging efforts of the photos – family portraits, home records etc. – taken by the tsunami and eventually rescued by the SDF (Self-Defense Forces).

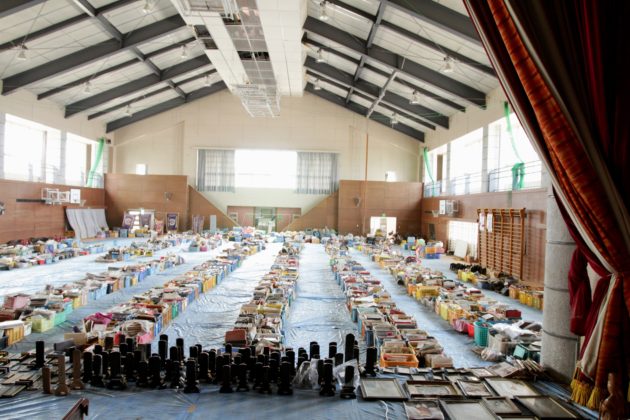

Responding to the summons, Takahashi contacted Professor Kuniomi Shibata, who led the Memory Salvage project, under the supervision of the FUJIFILM Corporation. At this time, the volunteers were still working in the Shibata room, at Otsuma Women’s University, and there were barriers to be circumvented so that people could search for the photographs on their computers – later two pieces of software were developed so that the images could be found according to facial recognition and area in which they were rescued. It was necessary to digitize them. However, the electricity supply was scarce and irregular, which means that they needed a way to do it without depending on the inconsistent power supply, that is, using digital cameras. The obstacle of the method, in turn, was the scarcity of equipment and the working environment. It was contaminated, full of small dust particles from the dry sludge that could damage the equipment, meaning that any tool would have to be donated, not borrowed. Incredulous, again, Takahashi sent a request to the web. The equipment was offered in a few hours, some by totals unknown to the photographer, others by colleagues and teachers at his photography school.

As the cleaning and digitalization process started to go smoothly, with 20 to 80 volunteers showing up every weekend, the reproduced photos started to accumulate. In this way, a space was created to return them to the owners. They were indexed and put back together in physical albums, with three images on their covers for identification by the former owner, providing the return of a portion of what was usurped by the disaster. By 2014, at least 300,000 physical photographs had been returned to their owners. Perhaps, like the character Hana, by writer Amós Oz, people cling to memory like someone who clings to a parapet, in a high place, and in a time when things are so ephemeral, they entrust memories to external devices because they want to leave evidence that identifies them.

Hopeless Box

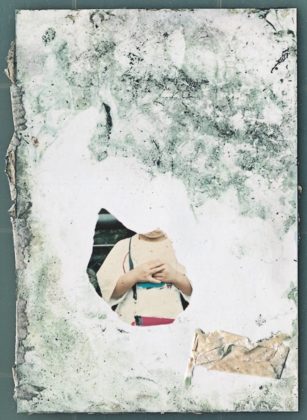

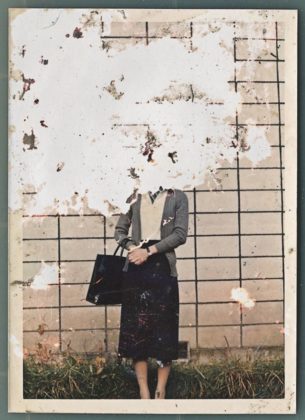

The photos arrived at the project washed, soaked and even completely obliterated. For a time, those that were considerably damaged, whose condition was practically impossible to be restored, were assigned to the Hopeless Box, a solution to leave them intact until the team found out what their fate would be, although more and more employees expressed that it would be better to simply discard them. As the campaign progressed, an issue that still hammered the heads of the organizers was the possibility of providing a financial return to the affected community. A temporary housing scheme was beginning to be implemented and needed funds to finance its construction and its workers. They agreed that it was significant to show these records to anyone who could not visit the collection.

One resolution was to expose the photos that were once lost, thus creating the Lost & Found Project, taking them from the International Photography Gallery, in Japan, to the Center for Contemporary Photography, in Australia, and the Aperture Foundation, in the United States. “We chose to show the photos in an exhibition format because we wanted people to see them face-to-face, not through printed matter or the internet”, reports Takahashi, noting that just before the exhibition went off the paper the organizers were still asking questions like: “What if we couldn’t raise enough money for the temporary housing communities? What if it was ethically wrong to show the photos publicly?”.

Following the opposite direction, the show has become a way of delivering a narrative about the people affected by the tsunami that fled a story filled with numbers that would involuntarily be translated into a tale about tragedy or a compelling allegory about hope in the face of chaos. Lost & Found – with records providing rich eminences of history, embracing a larger constellation of what remains of the tragedy and also visually impressive images as a result of its chemical deformation – provides a space for suspension in this dichotomy.

Why do we photograph?

“Why are people always taking photographs?” it is a question that seems to plague Munemasa Takahashi recurrently, at least throughout the writing of the book Tsunami, Photographs and Then.

Photography creates a reality that exists precisely in it, neither before nor outside it, it provides an indicative trace of who was there, as they looked like. Walter Benjamin would affirm that “in the cult of the memory of loved ones, distant or disappeared, the value of cult of images is the last refuge. In the fleeting expression of a human face, in old photos, for the last time emanates aura. That is what lends them that melancholy beauty, which cannot be compared to anything”.

If the photographs grouped for the Lost & Found project are well received by visitors, it may be possible to speak of a reframing of what these photographs have symbolized, moving away from an exclusive testimony of disaster, returning to approach a channeler of the universal issues of being human; as Ursula Le Guin wrote, of what is “in time’s womb, and death, and chance”.

Leia em português, clique aqui.

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025. Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025.

Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin e Jamile Coelho, a mostra reúne 20 artistas negras da diáspora africana e do continente africano, que se apropriam das artes visuais como campo de elaboração da memória e de reconstrução simbólica do mundo. Suas produções instauram um pensamento decolonial, no qual a arte atua como forma de escuta, reescrita e reexistência.

Participam: Amélia Sampaio, Barbara Asei Dantoni, Barbara Portailler, Beya Gille Gacha, Charlotte Yonga, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Enam Gbewonyo, Fabiana Ex-Souza, Gosette Lubondo, Josèfa Ntjam, Luana Vitra, Luisa Magaly, Luma Nascimento, Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt, Maria Lídia dos Santos Magliani, Myriam Mihindou, Na Chainkua Reindorf, Selly Raby Kane, Tuli Mekondjo e YêdaMaria.

Após itinerar por Bordeaux, Abidjan, Yaoundé e Antananarivo, a exposição chega a Salvador — cidade em que a herança africana se manifesta como fundamento estético e artístico — para instaurar um novo capítulo do projeto. No MUNCAB, essas artistas constroem um território de enunciação e reparação, no qual imagem, corpo e gesto tornam-se instrumentos de reconfiguração das narrativas históricas e de afirmação das subjetividades negras.

A exposição é uma realização do Ministério da Cultura, Petrobras e Embaixada da França no Brasil, em parceria com o MUNCAB, sob gestão da Amafro.

Serviço

Exposição | Memória: relatos de uma outra História

04 de novembro a 1º de março de 2026

Terça a domingo, das 10h às 16h30, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira: MUNCAB

R. das Vassouras, 25 - Centro Histórico, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá

Detalhes

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá de Min, Heitor dos Prazeres, Juarez Paraíso, Lita Cerqueira, Maria Apparecida Urbano, Rafa Bqueer e Rosa Magalhães.

A mostra no edifício Pina Contemporânea expõe 200 obras dentre adereços, projetos de decoração e documentação histórica em fotografia e vídeo, além de comissionamentos de projetos inéditos dos artistas Adonai, Ana Lira e Ray Vianna.

Dividida em quatro temas – Fantasia, Trabalho, Poder e Cidade, “Trabalho de Carnaval” apresenta a maior festa popular do país como uma cadeia produtiva que envolve o trabalho das muitas mãos desde antes mesmo da festa acontecer, ao mesmo tempo em que alude à precariedade e invisibilidade desses profissionais.

NÚCLEOS TEMÁTICOS

O núcleo Fantasia faz referência a dois elementos característicos do carnaval: o ato de se fantasiar e a força da imaginação. Projetos e croquis integram a parte central da Grande Galeria, como os estudos de J. Cunha para o carnaval de Salvador e Joana Lira para as decorações de rua do Recife.

Discussões sobre as condições de trabalho da festa são apresentadas no núcleo Trabalho, no qual são apresentadas obras que trazem à tona a representatividade dos trabalhadores.

A relação entre carnaval e espaço urbano ou rural aparece no núcleo Cidade por meio de representações de blocos, cordões, afoxés e outras formas de cortejos. O núcleo reúne obras como as fotografias realizadas por Diego Nigro no bloco de carnaval Galo da Madrugada (2025).

Por fim, o núcleo Poder celebra os encontros de trabalhadores dos canaviais em Pernambuco transformando-se em reis e rainhas do maracatu, assim como mulheres negras e grupos periféricos marginalizados se tornando, por alguns dias, as figuras de comando durante a festa na Bahia: Deusas de Ébano, Reis Momos, Rainhas do Carnaval.

Serviço

Exposição | Trabalho de Carnaval

De 8 de novembro de 2025 a 12 de abril de 2026

Quarta a segunda, das 10h às 18h

Período

Local

Pinacoteca Contemporânea

Av. Tiradentes, 273, Luz, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas.

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas. Os trabalhos, desenvolvidos com técnicas distintas como pintura, desenho, instalação e filme, dão continuidade à investigação do artista sobre a construção da identidade nacional, e suas contradições e influências, por meio de ícones e símbolos presentes na cultura brasileira.

O título da exposição surge da ideia de nascimento como marco de um momento, de uma nova existência sobre a Terra. Este evento milagroso também carrega a contrapartida da fortuna e da sorte, que nos acompanha desde a concepção. Para Obá, “Estar sujeito a isso não diz a respeito de uma escolha. Estar sujeito a isso diz a respeito de uma irreverência ao inevitável. Então, o que podemos fazer é demarcar essas várias sortes através do rito, da celebração, do símbolo, da linguagem.”

Cada obra que compõe a exposição confere a essa tentativa de situar a ideia de sorte, fortuna, ora como uma prece, ora com um ritual que celebra isso.

Uma instalação inédita, localizada em um espaço fechado, no fundo da galeria, se refere diretamente a ideia de jogo e de sorte. Nela, colunas de búzios se derramam sobre peneiras de bronze douradas, carregando ovos de cerâmica pintados de vermelho. Os búzios representam elementos de tentativa de leitura da sorte, do destino e da sina, e simbolizam a moeda de troca, que também se transforma em oferenda. Na disposição que se encontram no espaço, os búzios formam colunas que estão ascendendo, como um território de elevação espiritual e de ressignificação da vida ante ao que ela propõe de fatal.

Na entrada do espaço expositivo, um caminho de espadas de São Jorge e Iansã, conduzem até um novo objeto instalativo: um altar com dois troncos que simbolizam o pelourinho. Os troncos estão inteiramente cravejados de pregos — em um deles, os pregos estão voltados para fora; no outro, para dentro — simbolizando proteção e punição e a dificuldade de harmonizar tensões. Entre os pelourinhos, cabos suspendem uma cabeça de bronze com um prumo na ponta. Esta instalação é uma oferenda ao senhor do caminho, portanto, tem uma relação com Exu.

A instalação Ka’a porá (2024), apresentada pela primeira vez na mostra itinerante Finca-Pé: Estórias da terra no CCBB Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte e Brasília, ocupa lugar de destaque na exposição. Esculturas de pés, representando tanto o pé humano quanto o de uma árvore, enfatizam a conexão com o solo. A configuração da obra lembra um pequeno jardim, com troncos dispostos de forma aparentemente aleatória, cada um sugerindo uma direção diferente dentro de um labirinto. O título da instalação deriva do termo tupi ka’a porá, que se refere a um indivíduo que se estabelece e se ancora à terra. A expressão também remete à figura mítica da Caipora, protetora das florestas na mitologia indígena brasileira. Outro elemento simbólico da instalação revisita o conceito de poda, entendido aqui como um ato de violência que rompe com a vida e a natureza.

Telas de diferentes tamanhos e técnicas compõem a narrativa visual da mostra. Um conjunto de 22 pinturas de pequeno formato apresenta a leitura de Obá sobre o Tarô. Nas obras, o artista utiliza de uma mistura de técnicas junto a folhas de ouro, conferindo um tom mágico e fantasioso único às cartas do oráculo. Além dessas, a exposição reúne novas pinturas de grandes dimensões, bem como uma obra pintada diretamente sobre uma das paredes do espaço expositivo. Nessas peças, figuras e símbolos que compõem a identidade brasileira sugerem novas interpretações. A mostra também inclui desenhos inéditos feitos com carvão, nanquim, lápis e têmpera e sobre tela.

O filme Encantado (2024) apresenta uma performance do artista que propõe reflexões sobre sistemas simbólicos — especialmente os religiosos. A ação performática evoca uma perspectiva ritualística, centrada na figura do peregrino, que, em seu gesto, sintetiza elementos de crença, cultura e tradição associados ao imaginário do romeiro.

Com esse conjunto de obras, que atravessa diferentes mídias e simbologias, a exposição reafirma a potência da produção de Antonio Obá na construção de uma poética que investiga identidade, território e espiritualidade.

Serviço

Exposição | Nascimento

De 8 de novembro a 14 de março de 2026

Terça a sexta, das 11h às 19h, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Mendes Wood DM

Rua Barra Funda, 216, São Paulo – SP

Detalhes

A DAN Galeria apresenta a exposição O Brasil dos modernistas, com curadoria de Maria Alice Milliet. Reunindo cerca de 50 obras de emblemáticas de nomes fundamentais como Tarsila do Amaral,

Detalhes

A DAN Galeria apresenta a exposição O Brasil dos modernistas, com curadoria de Maria Alice Milliet. Reunindo cerca de 50 obras de emblemáticas de nomes fundamentais como Tarsila do Amaral, Di Cavalcanti, Cícero Dias, Victor Brecheret, Cândido Portinari, Guignard, Alfredo Volpi, Anita Malfatti e outros, a coletiva traça um panorama da arte moderna no país e destaca o papel do movimento que, a partir da década de 1920, redefiniu a linguagem artística nacional e acrescentou ao imaginário coletivo visões atualizadas do imaginário popular brasileiro.

O Brasil dos modernistas toma como ponto de partida das transformações que marcaram o surgimento da modernidade artística no Brasil, um movimento que se consolidou no confronto entre o conservadorismo cultural e o impulso de renovação de um país em transição. A Semana de Arte Moderna de 1922, é retomada aqui como marco simbólico desse embate: vaiada pelo público, expôs a resistência às novas linguagens e à ruptura com os padrões tradicionais, inaugurando uma produção voltada à atualização estética e à construção de uma identidade artística brasileira.

O percurso curatorial retrata como os primeiros modernistas, em busca de formação e reconhecimento, voltaram-se aos grandes centros artísticos da Europa. Foi a partir dessa experiência que muitos passaram a perceber a força e a originalidade da diversidade cultural brasileira para construção de suas próprias identidades artísticas. “Os nossos modernos não precisaram buscar em lugares exóticos os conteúdos populares ou étnicos que tanto encantavam os europeus. Encontraram em nossas paisagens e costumes os ingredientes para a constituição de uma visualidade de caráter nacional”, afirma a curadora Maria Alice Milliet.

Embora influenciada pelas vanguardas europeias, a arte moderna no Brasil manteve-se fiel à figuração. O contato com o movimento de “retorno à ordem”, no período entre guerras, levou os artistas a explorar linguagens expressionistas, cubistas e, mais tarde, surrealistas, em um processo que definiu as bases estéticas do primeiro modernismo brasileiro.

Dentre os destaques da mostra, está o Retrato de Judite (1944), de Alfredo Volpi. Pintado no ano em que o artista se casou com Benedita da Conceição, conhecida como Judite, o trabalho retrata sua esposa nua entre cortinas, de braços abertos, como se apresentasse as pinturas que a cercam. Volpi, que iniciou a carreira decorando fachadas paulistanas, desenvolveu uma linguagem própria, marcada pela geometrização e pelo uso refinado da cor. Seu trabalho simboliza a passagem da pintura figurativa para uma modernidade madura, iluminada e de forte identidade brasileira.

“É inegável que Tarsila, Di Cavalcanti, Cícero Dias, Rego Monteiro, Brecheret, Portinari, Guignard constituíram um corpus iconográfico identificado com o Brasil. Mais que isso, o modernismo acrescentou ao imaginário nacional visões atualizadas da nossa realidade sociocultural. Ou seja, quando pensamos na mulher brasileira, vem à nossa cabeça a sensualidade das morenas pintadas por Di Cavalcanti; a história da conquista do nosso território realiza-se no Monumento às Bandeiras, de Brecheret; nossos mitos são os de Tarsila; nossas praias são as de Pancetti; e as festas populares têm no colorido das bandeirinhas de Volpi sua melhor expressão”, completa Maria Alice Milliet sobre o eixo expositivo.

Ao reunir obras fundamentais do período, a mostra O Brasil dos modernistas destaca a relevância histórica e cultural do movimento que redefiniu os rumos da arte no país. A coletiva reforça o papel dessa geração de artistas na construção de uma identidade visual e reafirma a atualidade de seu legado na formação do que se entende por brasilidade.

Artistas presentes

Alberto da Veiga Guignard, Alfredo Volpi, Anita Malfatti, Candido Portinari, Cícero Dias, Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, Ernesto De Fiori, Ismael Nery, José Pancetti, Tarsila do Amaral, Vicente do Rego Monteiro e Victor Brecheret.

Serviço

Exposição | O Brasil dos modernistas

De 19 de novembro a 19 de janeiro

De segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, aos sábados, das 10h às 13h

Período

Local

DAN Galeria

Rua Estados Unidos, 1638 01427-002 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao longo dos anos, consolidou-se como cineasta, mas a fotografia continuou presente em sua trajetória, seja em seus filmes, seja nas instalações artísticas que produziu no século 21. Essa faceta de sua obra, ainda menos conhecida pelo público, é apresentada na mostra Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema, que abre no IMS Paulista, com entrada gratuita.

A exposição Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema reúne cerca de 200 fotografias tiradas por Varda, principalmente, entre as décadas de 1950 e 1960. O conjunto traz imagens clicadas em viagens, incluindo registros inéditos na China, em 1957, fotos em Cuba, no contexto pós-revolução, e nos EUA, onde a artista documentou os Panteras Negras. Há ainda fotos feitas em Paris, como as de uma peça encenada pelos Griôs, primeira companhia de teatro negro na cidade. Em diálogo, a mostra apresenta trechos de filmes da autora, enfatizando como o comprometimento social, o olhar afetuoso e o humor caracterizam a sua produção.

Serviço

Exposição | Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema

De 29 de novembro a 12 de abril de 2026

Terça a domingo e feriados das 10h às 20h (fechado às segundas)

Período

Local

IMS - Instituto Moreira Salles

Avenida Paulista, 2424 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres obras e documentos, incluindo pinturas, manuscritos inéditos, maquetes, desenhos e os célebres brinquedos de madeira produzidos pela família do artista uruguaio.

É a primeira vez que esse conjunto tão amplo e diversificado do artista é apresentado no Brasil, com peças que deixarão pela primeira vez as reservas técnicas do museu uruguaio, revelando ao público aspectos pouco conhecidos da produção do artista.

Com curadoria de Saulo di Tarso em colaboração com o Museo Torres García, a mostra aprofunda o entendimento sobre o “universalismo construtivo” e apresenta Torres García como um pensador de alcance global. A pedagogia do Taller Torres García, que defendia que os artistas da América Latina desenvolvessem uma arte própria sem depender das influências europeias e norte-americanas, também é explicada na exposição. A proposta era incentivar cada artista a buscar suas raízes, símbolos e referências locais, criando uma produção mais autêntica e conectada com a cultura do continente — algo que dialoga diretamente com a seleção presente na exposição.

Instituições como o Museo Torres García (Uruguai), o Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Barcelona), o Institut Valencià d’Art Modern [Instituto de Arte Moderna de Valência], o Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (Chile), além de coleções brasileiras como o MASP e a Pinacoteca de São Paulo, contribuem com empréstimos essenciais.

Este projeto conta com incentivo da Lei Federal de Incentivo à Cultura – Lei Rouanet e patrocínio da BB Asset.

Serviço

Exposição | Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos

De 10 de dezembro a 09 de março de 2026

Aberto todos os dias, das 9h às 20h, exceto às terças

Período

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025. Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin

Detalhes

O Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (MUNCAB) inaugura a exposição “Memória: relatos de uma outra História”, um dos acontecimentos centrais da Temporada França-Brasil 2025.

Com curadoria de Nadine Hounkpatin e Jamile Coelho, a mostra reúne 20 artistas negras da diáspora africana e do continente africano, que se apropriam das artes visuais como campo de elaboração da memória e de reconstrução simbólica do mundo. Suas produções instauram um pensamento decolonial, no qual a arte atua como forma de escuta, reescrita e reexistência.

Participam: Amélia Sampaio, Barbara Asei Dantoni, Barbara Portailler, Beya Gille Gacha, Charlotte Yonga, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Enam Gbewonyo, Fabiana Ex-Souza, Gosette Lubondo, Josèfa Ntjam, Luana Vitra, Luisa Magaly, Luma Nascimento, Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt, Maria Lídia dos Santos Magliani, Myriam Mihindou, Na Chainkua Reindorf, Selly Raby Kane, Tuli Mekondjo e YêdaMaria.

Após itinerar por Bordeaux, Abidjan, Yaoundé e Antananarivo, a exposição chega a Salvador — cidade em que a herança africana se manifesta como fundamento estético e artístico — para instaurar um novo capítulo do projeto. No MUNCAB, essas artistas constroem um território de enunciação e reparação, no qual imagem, corpo e gesto tornam-se instrumentos de reconfiguração das narrativas históricas e de afirmação das subjetividades negras.

A exposição é uma realização do Ministério da Cultura, Petrobras e Embaixada da França no Brasil, em parceria com o MUNCAB, sob gestão da Amafro.

Serviço

Exposição | Memória: relatos de uma outra História

04 de novembro a 1º de março de 2026

Terça a domingo, das 10h às 16h30, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Museu Nacional da Cultura Afro-Brasileira: MUNCAB

R. das Vassouras, 25 - Centro Histórico, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá

Detalhes

A última exposição de 2025 da Pinacoteca, “Trabalho de Carnaval”, é uma coletiva com obras de 70 artistas de diferentes gerações e origens, como Alberto Pitta, Bajado, Bárbara Wagner, Ilu Obá de Min, Heitor dos Prazeres, Juarez Paraíso, Lita Cerqueira, Maria Apparecida Urbano, Rafa Bqueer e Rosa Magalhães.

A mostra no edifício Pina Contemporânea expõe 200 obras dentre adereços, projetos de decoração e documentação histórica em fotografia e vídeo, além de comissionamentos de projetos inéditos dos artistas Adonai, Ana Lira e Ray Vianna.

Dividida em quatro temas – Fantasia, Trabalho, Poder e Cidade, “Trabalho de Carnaval” apresenta a maior festa popular do país como uma cadeia produtiva que envolve o trabalho das muitas mãos desde antes mesmo da festa acontecer, ao mesmo tempo em que alude à precariedade e invisibilidade desses profissionais.

NÚCLEOS TEMÁTICOS

O núcleo Fantasia faz referência a dois elementos característicos do carnaval: o ato de se fantasiar e a força da imaginação. Projetos e croquis integram a parte central da Grande Galeria, como os estudos de J. Cunha para o carnaval de Salvador e Joana Lira para as decorações de rua do Recife.

Discussões sobre as condições de trabalho da festa são apresentadas no núcleo Trabalho, no qual são apresentadas obras que trazem à tona a representatividade dos trabalhadores.

A relação entre carnaval e espaço urbano ou rural aparece no núcleo Cidade por meio de representações de blocos, cordões, afoxés e outras formas de cortejos. O núcleo reúne obras como as fotografias realizadas por Diego Nigro no bloco de carnaval Galo da Madrugada (2025).

Por fim, o núcleo Poder celebra os encontros de trabalhadores dos canaviais em Pernambuco transformando-se em reis e rainhas do maracatu, assim como mulheres negras e grupos periféricos marginalizados se tornando, por alguns dias, as figuras de comando durante a festa na Bahia: Deusas de Ébano, Reis Momos, Rainhas do Carnaval.

Serviço

Exposição | Trabalho de Carnaval

De 8 de novembro de 2025 a 12 de abril de 2026

Quarta a segunda, das 10h às 18h

Período

Local

Pinacoteca Contemporânea

Av. Tiradentes, 273, Luz, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas.

Detalhes

A Mendes Wood DM tem o prazer de apresentar a exposição Nascimento de Antonio Obá, que ocupa todo o espaço da galeria na Barra Funda com obras inéditas e emblemáticas. Os trabalhos, desenvolvidos com técnicas distintas como pintura, desenho, instalação e filme, dão continuidade à investigação do artista sobre a construção da identidade nacional, e suas contradições e influências, por meio de ícones e símbolos presentes na cultura brasileira.

O título da exposição surge da ideia de nascimento como marco de um momento, de uma nova existência sobre a Terra. Este evento milagroso também carrega a contrapartida da fortuna e da sorte, que nos acompanha desde a concepção. Para Obá, “Estar sujeito a isso não diz a respeito de uma escolha. Estar sujeito a isso diz a respeito de uma irreverência ao inevitável. Então, o que podemos fazer é demarcar essas várias sortes através do rito, da celebração, do símbolo, da linguagem.”

Cada obra que compõe a exposição confere a essa tentativa de situar a ideia de sorte, fortuna, ora como uma prece, ora com um ritual que celebra isso.

Uma instalação inédita, localizada em um espaço fechado, no fundo da galeria, se refere diretamente a ideia de jogo e de sorte. Nela, colunas de búzios se derramam sobre peneiras de bronze douradas, carregando ovos de cerâmica pintados de vermelho. Os búzios representam elementos de tentativa de leitura da sorte, do destino e da sina, e simbolizam a moeda de troca, que também se transforma em oferenda. Na disposição que se encontram no espaço, os búzios formam colunas que estão ascendendo, como um território de elevação espiritual e de ressignificação da vida ante ao que ela propõe de fatal.

Na entrada do espaço expositivo, um caminho de espadas de São Jorge e Iansã, conduzem até um novo objeto instalativo: um altar com dois troncos que simbolizam o pelourinho. Os troncos estão inteiramente cravejados de pregos — em um deles, os pregos estão voltados para fora; no outro, para dentro — simbolizando proteção e punição e a dificuldade de harmonizar tensões. Entre os pelourinhos, cabos suspendem uma cabeça de bronze com um prumo na ponta. Esta instalação é uma oferenda ao senhor do caminho, portanto, tem uma relação com Exu.

A instalação Ka’a porá (2024), apresentada pela primeira vez na mostra itinerante Finca-Pé: Estórias da terra no CCBB Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte e Brasília, ocupa lugar de destaque na exposição. Esculturas de pés, representando tanto o pé humano quanto o de uma árvore, enfatizam a conexão com o solo. A configuração da obra lembra um pequeno jardim, com troncos dispostos de forma aparentemente aleatória, cada um sugerindo uma direção diferente dentro de um labirinto. O título da instalação deriva do termo tupi ka’a porá, que se refere a um indivíduo que se estabelece e se ancora à terra. A expressão também remete à figura mítica da Caipora, protetora das florestas na mitologia indígena brasileira. Outro elemento simbólico da instalação revisita o conceito de poda, entendido aqui como um ato de violência que rompe com a vida e a natureza.

Telas de diferentes tamanhos e técnicas compõem a narrativa visual da mostra. Um conjunto de 22 pinturas de pequeno formato apresenta a leitura de Obá sobre o Tarô. Nas obras, o artista utiliza de uma mistura de técnicas junto a folhas de ouro, conferindo um tom mágico e fantasioso único às cartas do oráculo. Além dessas, a exposição reúne novas pinturas de grandes dimensões, bem como uma obra pintada diretamente sobre uma das paredes do espaço expositivo. Nessas peças, figuras e símbolos que compõem a identidade brasileira sugerem novas interpretações. A mostra também inclui desenhos inéditos feitos com carvão, nanquim, lápis e têmpera e sobre tela.

O filme Encantado (2024) apresenta uma performance do artista que propõe reflexões sobre sistemas simbólicos — especialmente os religiosos. A ação performática evoca uma perspectiva ritualística, centrada na figura do peregrino, que, em seu gesto, sintetiza elementos de crença, cultura e tradição associados ao imaginário do romeiro.

Com esse conjunto de obras, que atravessa diferentes mídias e simbologias, a exposição reafirma a potência da produção de Antonio Obá na construção de uma poética que investiga identidade, território e espiritualidade.

Serviço

Exposição | Nascimento

De 8 de novembro a 14 de março de 2026

Terça a sexta, das 11h às 19h, sábado das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Mendes Wood DM

Rua Barra Funda, 216, São Paulo – SP

Detalhes

A DAN Galeria apresenta a exposição O Brasil dos modernistas, com curadoria de Maria Alice Milliet. Reunindo cerca de 50 obras de emblemáticas de nomes fundamentais como Tarsila do Amaral,

Detalhes

A DAN Galeria apresenta a exposição O Brasil dos modernistas, com curadoria de Maria Alice Milliet. Reunindo cerca de 50 obras de emblemáticas de nomes fundamentais como Tarsila do Amaral, Di Cavalcanti, Cícero Dias, Victor Brecheret, Cândido Portinari, Guignard, Alfredo Volpi, Anita Malfatti e outros, a coletiva traça um panorama da arte moderna no país e destaca o papel do movimento que, a partir da década de 1920, redefiniu a linguagem artística nacional e acrescentou ao imaginário coletivo visões atualizadas do imaginário popular brasileiro.

O Brasil dos modernistas toma como ponto de partida das transformações que marcaram o surgimento da modernidade artística no Brasil, um movimento que se consolidou no confronto entre o conservadorismo cultural e o impulso de renovação de um país em transição. A Semana de Arte Moderna de 1922, é retomada aqui como marco simbólico desse embate: vaiada pelo público, expôs a resistência às novas linguagens e à ruptura com os padrões tradicionais, inaugurando uma produção voltada à atualização estética e à construção de uma identidade artística brasileira.

O percurso curatorial retrata como os primeiros modernistas, em busca de formação e reconhecimento, voltaram-se aos grandes centros artísticos da Europa. Foi a partir dessa experiência que muitos passaram a perceber a força e a originalidade da diversidade cultural brasileira para construção de suas próprias identidades artísticas. “Os nossos modernos não precisaram buscar em lugares exóticos os conteúdos populares ou étnicos que tanto encantavam os europeus. Encontraram em nossas paisagens e costumes os ingredientes para a constituição de uma visualidade de caráter nacional”, afirma a curadora Maria Alice Milliet.

Embora influenciada pelas vanguardas europeias, a arte moderna no Brasil manteve-se fiel à figuração. O contato com o movimento de “retorno à ordem”, no período entre guerras, levou os artistas a explorar linguagens expressionistas, cubistas e, mais tarde, surrealistas, em um processo que definiu as bases estéticas do primeiro modernismo brasileiro.

Dentre os destaques da mostra, está o Retrato de Judite (1944), de Alfredo Volpi. Pintado no ano em que o artista se casou com Benedita da Conceição, conhecida como Judite, o trabalho retrata sua esposa nua entre cortinas, de braços abertos, como se apresentasse as pinturas que a cercam. Volpi, que iniciou a carreira decorando fachadas paulistanas, desenvolveu uma linguagem própria, marcada pela geometrização e pelo uso refinado da cor. Seu trabalho simboliza a passagem da pintura figurativa para uma modernidade madura, iluminada e de forte identidade brasileira.

“É inegável que Tarsila, Di Cavalcanti, Cícero Dias, Rego Monteiro, Brecheret, Portinari, Guignard constituíram um corpus iconográfico identificado com o Brasil. Mais que isso, o modernismo acrescentou ao imaginário nacional visões atualizadas da nossa realidade sociocultural. Ou seja, quando pensamos na mulher brasileira, vem à nossa cabeça a sensualidade das morenas pintadas por Di Cavalcanti; a história da conquista do nosso território realiza-se no Monumento às Bandeiras, de Brecheret; nossos mitos são os de Tarsila; nossas praias são as de Pancetti; e as festas populares têm no colorido das bandeirinhas de Volpi sua melhor expressão”, completa Maria Alice Milliet sobre o eixo expositivo.

Ao reunir obras fundamentais do período, a mostra O Brasil dos modernistas destaca a relevância histórica e cultural do movimento que redefiniu os rumos da arte no país. A coletiva reforça o papel dessa geração de artistas na construção de uma identidade visual e reafirma a atualidade de seu legado na formação do que se entende por brasilidade.

Artistas presentes

Alberto da Veiga Guignard, Alfredo Volpi, Anita Malfatti, Candido Portinari, Cícero Dias, Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, Ernesto De Fiori, Ismael Nery, José Pancetti, Tarsila do Amaral, Vicente do Rego Monteiro e Victor Brecheret.

Serviço

Exposição | O Brasil dos modernistas

De 19 de novembro a 19 de janeiro

De segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, aos sábados, das 10h às 13h

Período

Local

DAN Galeria

Rua Estados Unidos, 1638 01427-002 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao

Detalhes

Nome central da história do cinema, com filmes que marcaram gerações, Agnès Varda (1928–2019) também é autora de uma extensa produção fotográfica, tendo inclusive começado sua carreira como fotógrafa. Ao longo dos anos, consolidou-se como cineasta, mas a fotografia continuou presente em sua trajetória, seja em seus filmes, seja nas instalações artísticas que produziu no século 21. Essa faceta de sua obra, ainda menos conhecida pelo público, é apresentada na mostra Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema, que abre no IMS Paulista, com entrada gratuita.

A exposição Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema reúne cerca de 200 fotografias tiradas por Varda, principalmente, entre as décadas de 1950 e 1960. O conjunto traz imagens clicadas em viagens, incluindo registros inéditos na China, em 1957, fotos em Cuba, no contexto pós-revolução, e nos EUA, onde a artista documentou os Panteras Negras. Há ainda fotos feitas em Paris, como as de uma peça encenada pelos Griôs, primeira companhia de teatro negro na cidade. Em diálogo, a mostra apresenta trechos de filmes da autora, enfatizando como o comprometimento social, o olhar afetuoso e o humor caracterizam a sua produção.

Serviço

Exposição | Fotografia AGNÈS VARDA Cinema

De 29 de novembro a 12 de abril de 2026

Terça a domingo e feriados das 10h às 20h (fechado às segundas)

Período

Local

IMS - Instituto Moreira Salles

Avenida Paulista, 2424 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres

Detalhes

A exposição internacional Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, inédita no país, celebra a trajetória de um dos pilares da arte moderna na América Latina, com cerca de 500 itens, entres obras e documentos, incluindo pinturas, manuscritos inéditos, maquetes, desenhos e os célebres brinquedos de madeira produzidos pela família do artista uruguaio.

É a primeira vez que esse conjunto tão amplo e diversificado do artista é apresentado no Brasil, com peças que deixarão pela primeira vez as reservas técnicas do museu uruguaio, revelando ao público aspectos pouco conhecidos da produção do artista.

Com curadoria de Saulo di Tarso em colaboração com o Museo Torres García, a mostra aprofunda o entendimento sobre o “universalismo construtivo” e apresenta Torres García como um pensador de alcance global. A pedagogia do Taller Torres García, que defendia que os artistas da América Latina desenvolvessem uma arte própria sem depender das influências europeias e norte-americanas, também é explicada na exposição. A proposta era incentivar cada artista a buscar suas raízes, símbolos e referências locais, criando uma produção mais autêntica e conectada com a cultura do continente — algo que dialoga diretamente com a seleção presente na exposição.

Instituições como o Museo Torres García (Uruguai), o Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Barcelona), o Institut Valencià d’Art Modern [Instituto de Arte Moderna de Valência], o Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (Chile), além de coleções brasileiras como o MASP e a Pinacoteca de São Paulo, contribuem com empréstimos essenciais.

Este projeto conta com incentivo da Lei Federal de Incentivo à Cultura – Lei Rouanet e patrocínio da BB Asset.

Serviço

Exposição | Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos

De 10 de dezembro a 09 de março de 2026

Aberto todos os dias, das 9h às 20h, exceto às terças